Ravenna is all about early Christian churches and mosaics. They make a big thing of them – even incorporating them into their street signs – and there are frequent groups of tourists being led around the sites , all wearing headphones, with someone muttering into a microphone. Most of the people on the tours we saw seemed to be either chatting or on their phones, so you do sort of wonder how interested they really are.

Ravenna’s development (and arguably claim to fame) spans an incredibly complicated period of history and an equally complicated period in the early Christian church. I have tried to piece some of it together (with limited success – I can’t keep the names straight) so I’m not even going to try to pass on my soupçon of knowledge. Furthermore, as a consequence of unsupportive lighting, crowds and a mobile phone rather than a proper camera, the photographs do not, in any way, do justice to the beauty of the mosaics.

These are impressions – mine (and Roger’s).

Unfortunately we started with the most impressive two examples and the rest lost their lustre in comparison. To anyone thinking of visiting, leave our first two until the last!

The Mausoleum of Galla Placidia is a tiny, inconsequential looking church whose rather diminutive and bland exterior belies the wonder of the interior. It was built by Theodosius 1’s daughter (Galla Placidia) in the early part of the fifth century (yes, that’s almost 1600 years ago) and was supposed to house her body after death (she actually died in Rome and was probably buried in her family’s vaults in the original St Peter’s).

That it has survived is a miracle, especially when you learn that part of the front portico was destroyed putting a road through between it and the church it was originally linked to (also commissioned by Galla Placidia).

The church is cruciform, with a central dome and arches in every arm of the cross. Every portion of every curve – ceiling, arch, end of arch – is mosaic, with dark blue and gold predominating. As soon as you lift your eyes (after they have acclimatised to the low light), rich colour enfolds and encloses but it avoids being oppressive because there is so much detail to chase. Regardless of your views on Faith, the artistry and workmanship are breath-taking (we both gasped).

A word of warning: no selfie sticks. The guard got quite agitated and shouty as one tourist extended her selfie stick to about 2 metres and waved it at the ceiling. Everyone involved was Italian and it all got a bit loud.

Close by is the Basilica of San Vitale. It was completed during the reign of Justinian and consecrated in 547. It’s a much larger affair, with several levels inside arranged around a central dome. What first catches your eye is the high altar – you can’t really avoid it. Justinian had himself and his wife Theodora included in the panels either side of the altar.

But it’s worth noting that the floors are also original (well, in most places) and of different types of mosaic. There are the small piece mosaics (what I think of as ‘Roman’ mosaics) on most areas and also the larger piece ones (which date from the same period) which are used in the area under the central dome. Apparently the Romans didn’t just use little bits of tile, they also used big bits.

The columns are also interesting as they appear to be painted but are, in fact, marble tiles – 1400 year old Rorschach ink blot tests! But you can see the joins if you look closely enough.

An interesting set of churches are those linked to Theodoric, an Arian Ostrogoth who ruled the Western Roman Empire from Ravenna for 30-ish years until his death in 526 – he overlapped a bit with Justinian, who ruled in Constantinople. Theodoric was a tolerant king, who built churches for Arian worship but also allowed Roman Christian churches.

(In stark contrast to Justinian, who after Theodoric’s death, suppressed Arian worship.)

Theodoric’s Baptistry is tiny (even smaller than Galla Placidia’s Mausoleum) but with an amazing (yes, domed) ceiling.

Apparently what’s important about this mosaic (other than its beauty) is that it’s one of the first times the apostles are shown with halos. And their hands are covered as a sign of respect. Who knew?

Staying on the theme of Theodoric, he also had a palatine church built (connected to his palace, for his own worship) – the Basilica of Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo.

This is large and has had some ‘adjustments’ and additions made by later rulers – the earliest being Justinian who ordered certain portions of the mosaics to be removed because he didn’t approve of the iconography. What is left of the original mosaic work runs on either side of the main body of the church – portraying, in places, ordinary life in Ravenna at the time.

At one end of the procession of saints and people you can see the remnants of hands and arms, left when the figures were replaced with curtains. The whole altar area was also tiled but these were removed in the 16th century. Pity.

There are several other (important) churches with mosaics – we visited most of them, I’ve included one more here simply because this is turning into a treatise on Byzantine mosaics (and Ravenna has both earlier and later mosaics).

The Orthodox Baptistry (or Baptistry of Neon) is a Roman Christian church dating from the late fourth, early fifth century. It is small with an enormous granite font in the middle of it and lovely mosaics (yes, domed again).

A word on sinking buildings…

Ravenna is built on marshes – much like Venice but without the canals (which are outside the main town) – you step down several steps into the Basilica of San Vitale and Theodoric’s Baptistry. The sinking in the Orthodox Baptistry is marked – on its third floor.

In both the Baptistries and the Galla Placidia the mosaics are significantly closer (like three metres closer). Would they have been more or less effective further away?

Ravenna does have some Roman mosaics, discovered when investigating the drainage under a (you guessed it) church (but not an early one this time). They are on show, and what is noticeable is the high-tec excavation and presentation, versus the general decrepitude of the church above them – there was ivy growing through the windows.

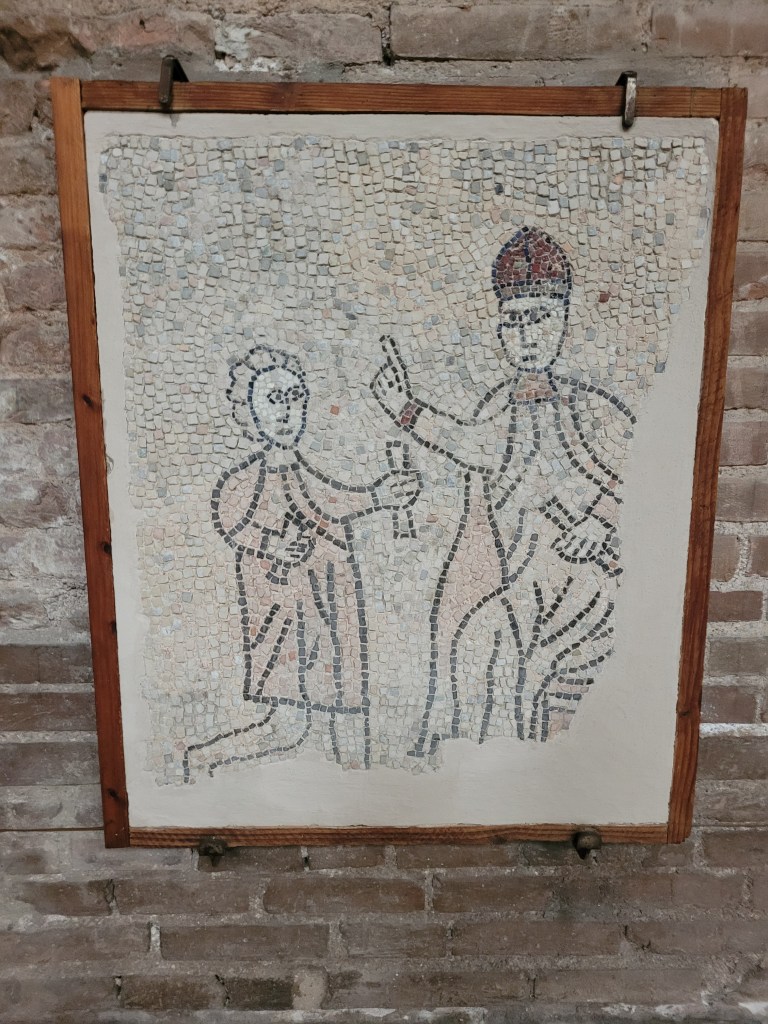

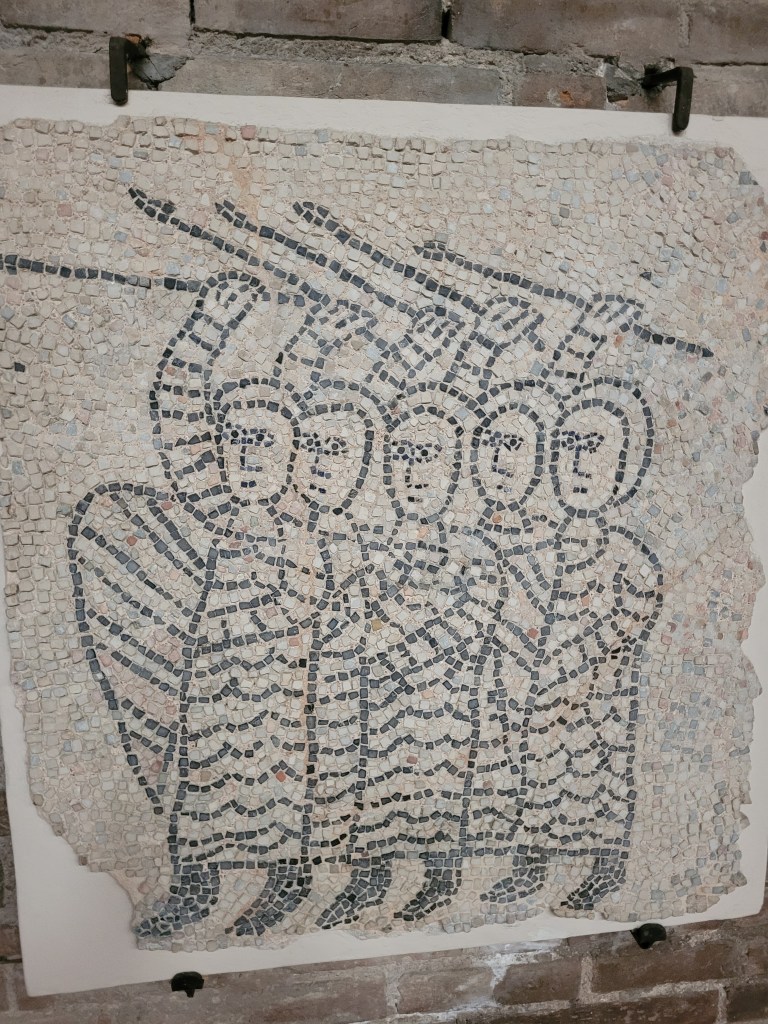

My final word on mosaics is about those found in San Giovanni Evangelista. This was one of the earliest churches in Ravenna and, like the rest of them, had been generously decorated with Byzantine mosaics. These were removed in the 16th century and have, mostly, been lost. The church stood until an Allied bombing raid during WW2, when it was destroyed. During the rebuilding, the thirteenth century floor of the nave was resurrected and placed in panels on the walls of the church. They depict scenes from the disastrous Fourth Crusade, when Constantinople was sacked.

(Swift reminder – Constantinople was a Christian city, Eastern Orthodox, but Christian nonetheless. It was sacked by Western Christian so-called knights, who raped, pillaged, thieved and burned their way through the city in a wonderful display of religious tolerance.)

In a mosaic Bayeaux tapestry of line drawings, they tell the story of these Crusaders and depict some of the fantastical creatures they ‘saw’.

Ravenna has a fascinating, complex and important history. We do have a book (printed, not digital) JUST about Ravenna: it’s a paperback and between two and three inches thick. At some point I will (honest) read the book and then return to Ravenna so that I can make better sense of it all.

Leave a comment