El Taburiente national park was designated as such in the late 1950s and the park occupies most of the caldera formed by the Taburiente volcano and the various vents and volcanoes that surrounded it. Fun fact, ‘caldera’ for the centre of an extinct volcano was coined in the early 1800s by a German geologist, after visiting El Teide (on Tenerife) and the El Taburiente crater here on La Palma.

Stick with me, this WILL connect – eventually.

For a long time, sugar cane was the most important money-making crop in La Palma. This became replaced with bananas (and there are still a lot of banana plantations) and now this is being replaced with tourism. One of the big draws to La Palma (other than the lovely winter weather) is that the whole island has been declared a UNESCO biosphere reserve, so hiking, walking, cycling and camping are major focuses.

As a consequence, there are plenty of volcano (and other) walks, including one that starts in El Taburiente and goes down the spine of the island, from volcano to volcano. It’s called ‘Ruta de los Volcanes’ (route of the volcanoes), funnily enough.

A really famous stop on the volcano sightseeing trip is Mirador de la Cumbrecita, which is where some of the well known pictures of La Palma are taken. Because it’s close to Santa Cruz, it gets very busy and you have to book a parking slot, for a given amount of time. We did know this, it’s in the guide book, we just didn’t think it would matter in February. It did.

Instead we went to the Visitor Centre, where we learned things about La Palma in general, volcanoes and lava. The only thing I can remember about lava is that I should have been talking about pumice in the previous blog and if said pumice is in small enough pieces, it’s referred to as ash. The setting was phenomenal, the clouds were moving FAST and by the time we left (about 30 minutes), the sky was covered in clouds.

Weather is a tricky thing in the caldera (another thing I learned). Apparently it’s always clear blue skies first thing in the morning, then as the temperatures rise, clouds come in on the Trade winds from the North East and fill the caldera. They burn off again by late afternoon, leaving clear skies overnight.

There were other nuggets, but I don’t remember them (there was a lot of information)

It was windy again (even windier) so on the recommendation of the visitor centre staff, we drove to Barranca de Angustias (Ravine of Anguish) – a wonderful name.

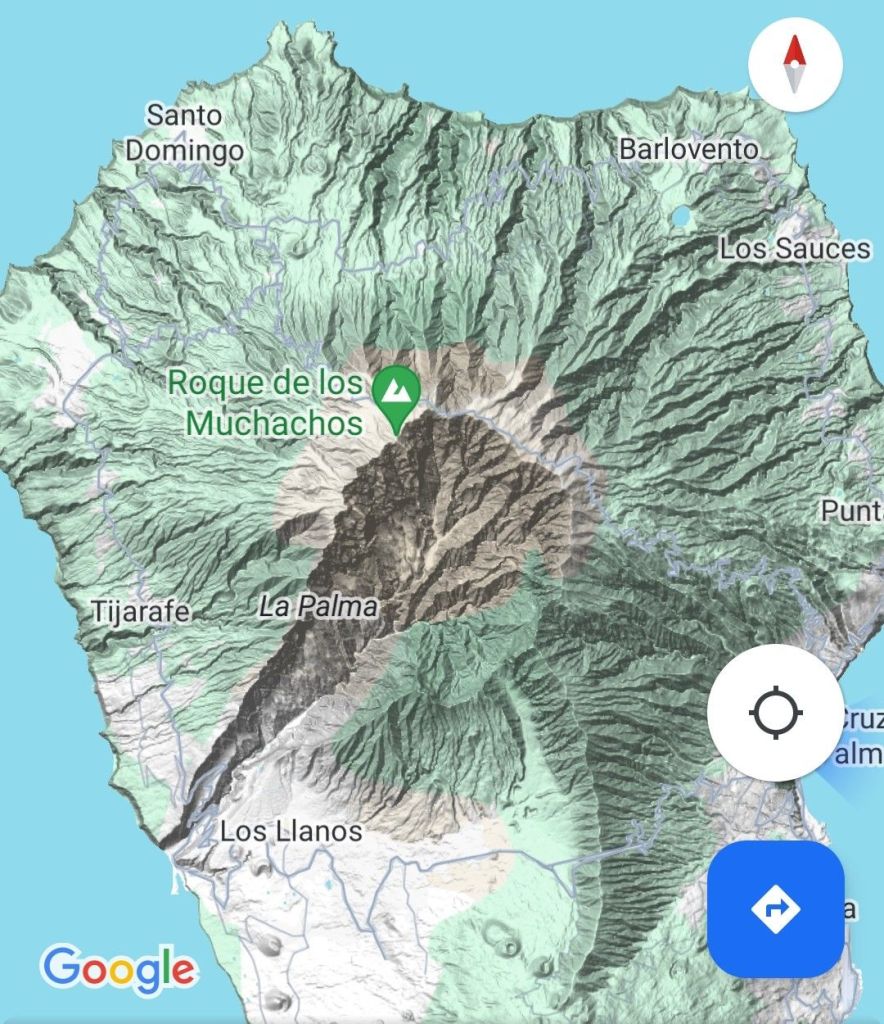

If you look at the map, the barranca goes up West to East through the ravine that runs to the sea. And it would appear that most of the drainage runs through this ravine.

When the rim of the crater finally collapsed (a long time ago), most of the debris followed this line west into the Atlantic. Presumably, the action of water then deepened the ravine.

Once again I was glad Roger was driving, as the road into the Barranca was steep, tight hairpin corners, no barriers and very narrow. Fortunately we only met one car driving up.

Parking was at the very bottom, in a area surrounded by warning signs of ‘inundacion’ (yes, inundation). Thankfully it looked dry as a bone.

When we located our trail – a 6 Km walk to the Cascada Colorada (coloured cascade), with only 250 metres of elevation – it was blocked off with red and white tape and a no entry sign. The other options were to walk into up the Barranca on the dry river bed (past very large no entry signs and white X markings) or to try the trail up the opposite side to Berencitas – which we knew might be steep.

Despite the aches and pains from the long downward trek yesterday, we thought we would give it a go. How hard could it be?

Very!

After 45 minutes of mostly straight uphill, in blue skies (where did the clouds go?), we paused to check the map and realised we had covered less than one kilometre of the walk – roughly a sixth of the whole route.

We walked down on the road as the trail was steep, dry and slippy.

But we got some good views on the way down!

Once back at the bottom, we ignored the warning signs and walked up the river bed. Then found the ‘desviacion’ sign that signalled the detour for the very short section of our original route. There hadn’t been any indication that there was a detour!

So on we went up the barranco.

Sometimes the route went along the river bed, sometimes it went above it. The views were good either way.

Event, the path got too narrow with too many vertical drops alongside (with no protection), plus we had very little water left and I was reluctant to go on without a better supply. So we turned back.

Although this section was mostly flat (with a bit of clambering when the path moved up above the river bed), the going underfoot wasn’t totally easy. As we moved further up, the dry river bed turned into a trickle and then a stream, and we had to constantly move from side to side. The further up we went, the deeper and faster the water and the greasier the stones (and bits of wood) we used to cross. There were also lots of large, loose pebbles and rocks that made the footing difficult, along with some massive boulders.

When there is a major flood of water, it must be an amazing sight!

Taking both subsections of walk together, we felt suitably exercised and deserving of lunch.

For the most part, the walking routes were well signposted. La Palma sees senderismo (walking/hiking), particularly around the volcanoes, as a major tourist draw and it’s easy to see why.

Leave a comment