As you fly over Tenerife, large earth coloured polytunnels show up around the coastline; unexpected, considering the sunny warm climate – and some really are large.

This oddity is even more marked on the south side of the island, where the earth is rocky and bare, there is more sun and it’s hotter – yet they are still numerous and large.

But after a few days, it dawned on me that it was about protection from the wind for the banana plantations – the plants are vulnerable to wind damage.

One of the major exports of the Canary Islands is bananas, with plantations on every island we visited and some of them cover every spare flat surface and some terracing.

Bananas only grow at low altitudes – so by the sea – which, in turn, means wind. So they need protection. Initially this was done by raising the plants in walled ‘fields’: walls with air bricks around the top third to allow for air flow. The bricks are varied in design, some just holes, some more ornate (probably the older ones). Then they discovered plastic netting.

In sheltered places, the difference between new leaves and older leaves is visible: new growth leaves are whole, older leaves are shredded by the wind. This isn’t good for productivity, hence the expanses of plastic netting in more exposed places. It seems counterintuitive to attach such economic importance to such fragility.

The trees bow under the weight of the single fruiting body; as a result, those plantations that are visible (ie not surrounded by netting or walls) are a rustling mass of tattered pompoms, slim poles and weird fruiting bodies.

In some plantations they put plastic bags over the fruit (to ripen? for protection?) and sometimes it looks like the fruit hasn’t developed properly – both of these make for an even odder appearance.

I love bananas but they seem to consume a lot of attention and resource in order to make them possible.

Another feature of the islands is the prevalence of the Nopal cactus (already mentioned in previous posts). While some use is being made of the fruit (prickly pears), my initial response was to see these as an invasive foreign species that should be eradicated.

In fact, this species was deliberately imported in the 16th century in order to farm the cochineal beetle, which was then harvested for its dye. Canary Island cochineal has the Protected Designation of Origin ‘Cochinilla de Canarias’: support has been given to save this traditional farming industry, which was almost extinct at the start of the 21st century. Both beetle and cactus originated from Mexico.

While I like the idea of supporting local traditions, I am not convinced about how this applies to an incredibly invasive species which seems to be edging out local flora and fauna. Hopefully, they can make it work.

Another New World import (Brazil, then Peru) much in evidence is the bougainvillea shrub. It’s also invasive: I am aware of the hypocrisy of loving one for its sprawling ebullient colour and loathing the other for its unsightly shape and spines. (Yes, I am also aware that bougainvillea can be spiny, but the spines aren’t on show!)

As a child in Mexico, purple bougainvillea was the only colour I saw. As an adult travelling around Mediterranean Europe, the range of colours astonished (and delighted) me.

Bougainvillea has spread widely and spontaneously hybridised into shrubs that can bear multiple colours on one branch. They can be clipped into a hedge, controlled and shaped (although formal topiary is probably beyond them) and left to burst over balconies, walls and even abandoned machinery. I adore them.

The only colour I didn’t see on this trip was pale yellow.

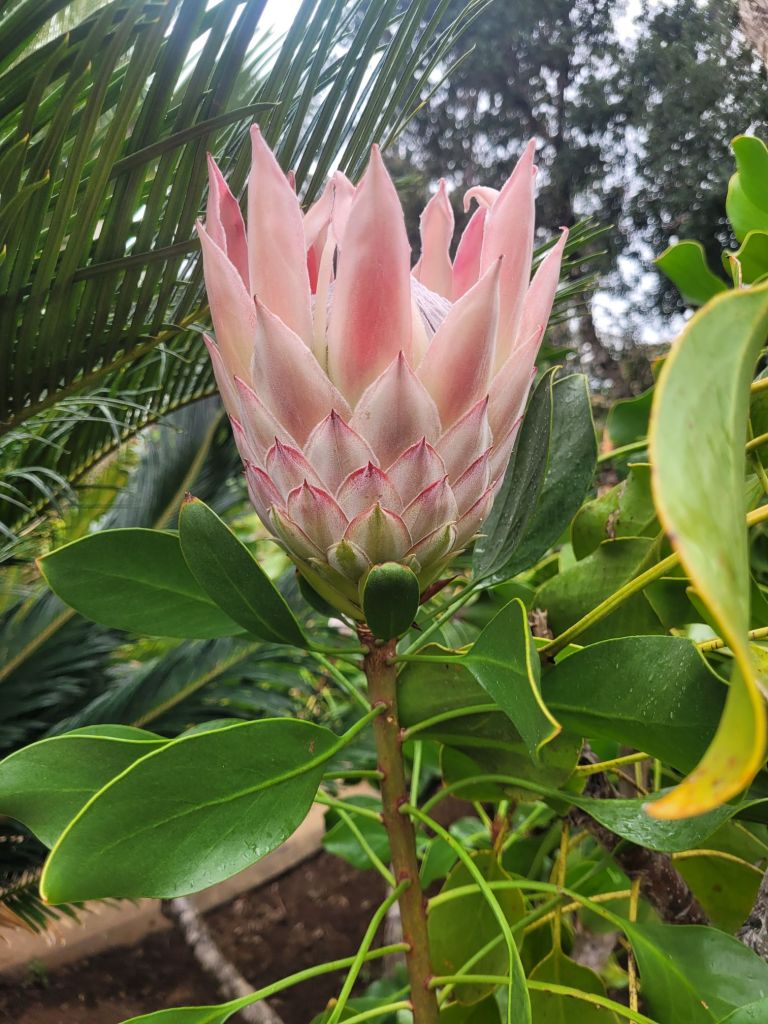

Other noteworthy plants we saw were a papaya tree (yes, South America again) on the coast and something that looked rather like an artichoke flower but had the wrong shaped leaves – this was up in the mountains.

Acknowledgement of the Guanches peoples who inhabited the island before European invasion is patchy and sometimes contradictory. On La Palma, the visitor centre in El Taburiente commented on the ‘ignoble’ behaviour of Conquistadores who tricked the Guanches into submission – through slaughter and violence into slavery and death. However, also on La Palma, the Naval museum exhibit notes remarked on the ‘peaceful and tranquil’ subjugation of the natives. On La Gomera, a statue to the leader of the Guanches’ (futile) resistance against the Spanish stands on one of the more popular beaches, back to the west, facing inland – most of the Guanches on La Gomera were slaughtered.

And while there is a museum on Tenerife about the Guanches, it’s small and was being remodelled, while the museum about the history of the island is large and avoids much mention of the Guanches.

Possibly something that needs some work.

These two weeks were about exploring options for winter sun. It’s been interesting and two important things have become evident: firstly, we don’t like vertiginous walking trails and secondly, we need to adjust our expectations of ‘winter sun’ in the northern hemisphere (and I need to pack less and more appropriately).

Yes, the weather has been better and warmer than in the UK but the walking trails tend to be at higher altitudes, which means cooler temperatures and wetter conditions.

The warmest weather is on the south and southwest sides of all the islands we visited: these are invariably the most developed and touristy. In the case of Tenerife, this means Los Cristianos and Playa de Las Americas. Crime rates are high here, with involvement from various mafia groups, drugs and violence (mostly between drunk English tourists). The beach looks incredible; the surrounding area is definitely not our cup of tea. But if you want warm sun and a golden sandy beach, that’s where you will find it. Even when the rest of the island is under cloud.

We found the food and wine better across the board than in Madeira, with a wider range of fish (although a less broad range of fruit). The hotels have been more mixed – some lovely, some ‘less lovely’. The ferries have been easy, although sometimes crossings have been rough.

Overall, the Canaries have a slightly Wild West feel about them (outside of the tourist areas) and the spanish has a more New World accent; whether that’s because of recent inward migration from South Anerica or earlier imports, I don’t know. Like Andalucian spanish, it gets so fast I can’t follow it at all.

I wish I had seen more cetaceans and I also wish I had seen La Palma’s famous ‘starry skies’ (or starry skies anywhere, really).

Those stay on the bucket list.

Next up is Northern Spain – by train one way.

And, of course, the weather was gorgeous on our drive to the airport. Sod’s Law!

Leave a comment