Well, the northwest of it at any rate.

Mention ‘La Rioja’ and everyone immediately thinks of the wine – and yes, it’s a region well known for its wines (some of which are eye-wateringly expensive). But there is a lot more to this region, small as it is.

We both sort of expected that once we passed the sign indicating that we were in La Rioja, we would immediately see loads of vines – not quite. Instead we saw a lot (a LOT) of very flat agricultural land that was either wheat (or some other kind of grain) or rapeseed.

And it didn’t change much even when we got to Santo Domingo de la Calzada – mostly large fields of different kinds of crops.

But La Rioja has other claims to fame: the Camino Francesa runs through this area (there are a lot of pilgrims) and it’s also home to a monastery that is not only dedicated to one of Spain’s patron saints but also the place where ‘Spanish’ as a distinct language, was thought to have been first written down.

The Camino was immensely influential. Santo Domingo de la Calzada, where we based ourselves, was formed around a stopping place for pilgrims making their way to Santiago de Compostela. The saint who gives his name to the town (and who, so the story goes, founded the ‘hospital’) wanted to be a monk but wasn’t accepted by the local monastery; he became a hermit instead, close to one of the crossings of the River Oja. Watching the pilgrims struggle across the river on their journey inspired him to build a ‘calzada’ – a bridge – to ease their journey. He then built a ‘hospital’ (a resting place for pilgrims – and then for the infirm) and a small church.

Of course, pilgrims were big business and our cynicism is such that we couldn’t help but feel that a resting place and a nice river crossing for pilgrims fit into a business model somehow. But he was held to be incredibly holy: an apocryphal story tells of a miracle involving (after other things) a couple of roast chickens coming back to life: the cathedral still houses two live chickens in a special coop.

The old part of town is pretty – they have medieval walls in existence somewhere.

And the church is large (as one might expect in any Spanish town but especially one that houses chickens). The cathedral had a collection of silver and gold linked to worship or church decoration which I found it difficult to walk past. Once again, all that wealth in a time when most of the people were so poor. It really did not leave a good impression on me.

The reliquary altar piece grossed me out a bit – it was the transparency of the individual reliquaries that was a bit much.

There were, however, two things we really liked about this cathedral. The chickens (obviously) and the way they dealt with the remaining Romanesque chapel of St Peter, dating from the late 12th century. It had been blocked by the main altarpiece in the 16th century. On initial viewing the later piece seems traditionally blingy, but closer inspection reveals grotesques and mythological creatures unkown in other altarpieces throughout Spain. But it is certainly blingy and its removal in 1994 to a side chapel allows the oldest part of the church to be appreciated.

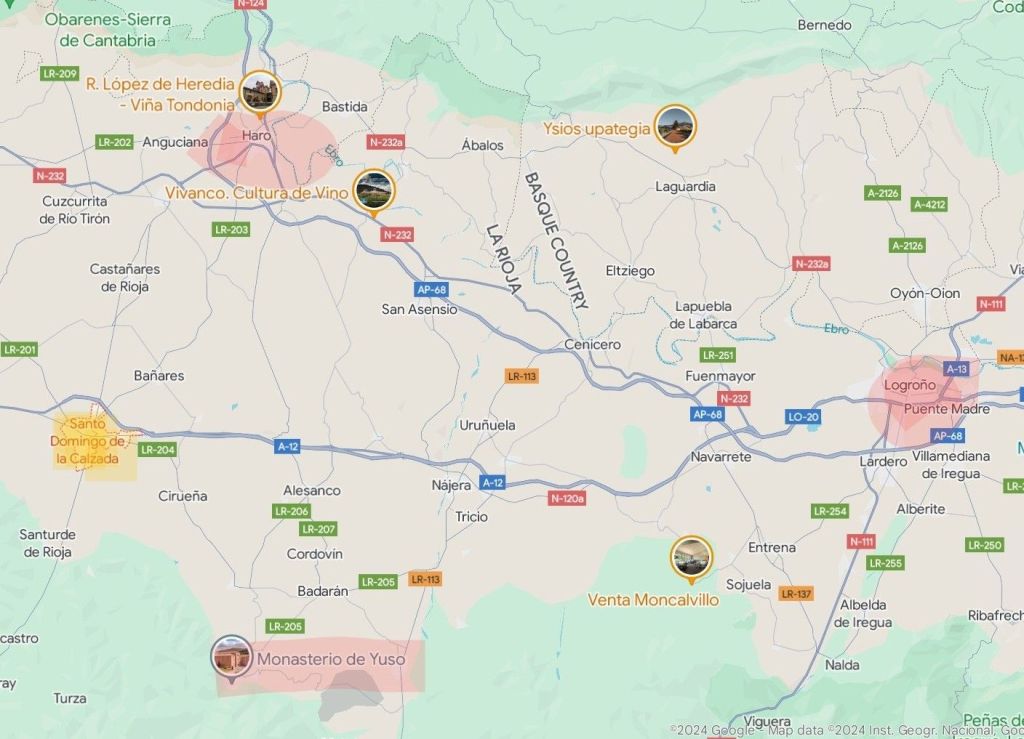

We saw pilgrims regularly. Such was/is the demand that the Parador chain has two of their hotels in Santo Domingo. Haro and Logrono also had pilgrims: pilgrim hostels, pilgrim signposts, scallop shells in the pavements… but they are both also closely involved with the wine trade.

Haro was on the list because it’s a major wine town and also where Roger’s Spanish teacher came from. It’s small, has a pretty square, a large number of wine warehouses (many of which had spent money to tart up their warehouses in order to exploit wine tourism). Most importantly, it’s on the Ebro and is surrounded by vineyards – finally!

After a coffee (we didn’t feel we needed to spend any longer there) we went to Logrono, the capital of La Rioja. Historically, Logrono was an important stopping place for those travelling along the Camino (although it doesn’t have any nice chicken stories or the equivalent) but it was also an important ‘passing through’ place generally. Little is left of its Roman heritage (it was known as Vareia) and during the early medieval period Logrono was fought over by the kings of Navarre and Castille (well, it was also a commercial port on the river Ebro, so that’s not surprising).

It’s a BIG place, with a lot of urban development around it. As might be expected in a large pilgrim town, the cathedral is vast and apparently has a painting attributed to Michelangelo. Sadly it was closed when we walked around it – we even tested doors, honest!

The streets around the cathedral are pretty.

I have to say that I have never seen quite so many people wearing flip flops or sliders in cool temperatures (it wasn’t warm), many wore their sandals with thick socks and those that didn’t sported a fascinating range of blister plasters on a variety of positions on their feet.

The Ebro is wide here – you can see that it might have been navigable. The iron bridge was built in the late 19th century, after an unfortunate accident where the older, stone bridge collapsed under the weight of the railway.

Haro and Logrono were interesting to walk around and we had a nice lunch in Logrono at La Cocina de Ramon but the ‘jewel in the crown’ was San Millan de la Cogolla, just south of Santo Domingo.

San Millan itself is small and fairly insignificant but it is home to the Monasteries of Yuso and Suso, which are utterly fascinating.

San Millan was an anchorite who lived in a cave up in the hills next to what is now the village. Interestingly, he was an Aryan Christian (it’s complicated and there isn’t time in this blog to go through the whole Aryan heresy – an aside, it’s only a heresy from the Catholic point of view) a religion brought to Spain by the Visigoths who moved into Spain in the early fifth century (replacing the Romans). Such was the extent of San Millan’s influence that he (an Aryan Christian) became one of the two patron saints of Spain. After his death in the sixth century, his followers created a monastery next to the cave he had inhabited and this became a place of pilgrimage in its own right, plus a place of learning.

Eventually this monastery (Suso – derived from the word for ‘higher’) couldn’t cope with the influx of people and with no room to extend it, they built a new, larger one at the bottom of the hill, near the river (Yuso – derived from the word for ‘lower’). That was a Romanesque monastery; it was razed in the sixteenth century to make way for a very large monastery built by and for the Benedictine order and housed up to 200 monks.

It’s the Romanesque monastery (11th century) where things get interesting for the Spanish language. At the time, a development of vulgate Latin was spoken – we were told this is called ‘Romance’ but I have my doubts this is quite correct and I don’t have the sources at present to check. Either way, what was spoken was not what was written in the prayer books, gospels and teaching stories read to the local people – these were written in Latin and the people couldn’t understand them. So the monks started to annotate (or ‘gloss’) the texts with single word translations and then with phrases and then with full translations – all in the local language (which would then go on to become Spanish). These sorts of things pop up all over the north of Spain round about this time but in this particular monastery there was a series of syntactically complete sentences, in the local language (I’m not calling it Romance until I can check it) that were a ‘new’ prayer rather than just a translation. This is taken to be the first instance of early Spanish.

The monks were studious, productive and spread their influence far and wide through the north of Spain – our guide to the monastery made a claim for ‘La Rioja’ to have derived from ‘de la Oja’ – both the river that runs through the area and ‘of the page’ as the monks circulated writings and documentation.

There was much more that was interesting – they hold one of the three complete collections of song books in Spain (complete as in the whole cycle of the church year).

There was extensive use of alabaster for flooring and alabaster dust/rubble for filling walls. The room where they kept the books had no extra air-conditioning or fans to keep the air circulating – the building itself kept everything dry. The chapter house has an alabaster floor, it was decorated in the mid-18th century and has not been renovated or ‘touched up’ at all. Yet it seems in perfect condition – again, the floor keeps the air dry because alabaster is so porous.

In the 1820s, when the Spanish government dispossessed the monks and nuns in the large convents and monasteries, they quickly realised that the buildings at Yuso were too large and too expensive to maintain. The Benedictines refused, so the Augustins took over and used it to train overseas missionaries. It was very absorbing, even the church, which had a large oriol window that, at one of the solstices, shone through a round part of the choir fencing to produce a large circle of light in the middle of the church.

But of course, the Camino and those on other pilgrimages still played a large part in this place too. What was the ‘hospital’ is now a four-star hotel – so still welcoming guests!

There is much more to La Rioja than the wine!

Leave a comment