‘Salzburg’ apparently means ‘salt mountain’ (or ‘salt hill’), which seems a trifle hyperbolic until you visit Hallstatt. Which is, literally, a mountain of salt.

Around 250 million years ago, the area that is now the Alps was a shallow sea called Tethys; as it dried out, a large deposit of salt was laid down. Formed by the collision of the African plate colliding with the European plate, a free standing cone of 62% rock salt resulted (along with the Alps). This deposit has been exploited since Neothilic times – initially from the salty springs that emerged from the deposits and then from mining.

Like much limestone, the area abounds in ‘fishy’ fossils.

I do wonder what earlier peoples made of them.

Between 1400 BCE to about 330 BCE, the area above Halstatt village was mined using antler picks, then bronze and finally iron tools. Chunks of rock were hewn out of the earth, carried up to the surface and ground down, possibly refined in some way (no, this wasn’t mentioned anywhere but it makes sense) and exported around Europe.

Another use of the salt was to cure pork. The animals were brought up the mountain, butchered, and various cuts buried in rock salt for a period of time. This semi-cured meat was then taken down into the mine and hung to finish the curing process in a more predictable environment – both in terms of temperature and moisture. These cured slabs of meat (ie bacon) were, again, exported around Europe.

Remember, this is still around 800 BCE!

As a result of the preservative nature of salt, anything dropped or left in the mines (textiles, foodstuffs, tools, bodies) and discovered subsequently, has been in an excellent state for investigation. The textiles are particularly interesting, as are the shoes (which look almost exactly like North American moccasins). The salt makes it difficult to date these artifacts, but the museum gives a range of 800 – 300 BCE.

In 330 BCE a disasterous mudslide/landslip filled the various mine shafts with mud and rubble. Attempts were made to re-open the shafts but they ended up driving a new shaft down to the salt from higher ground: this has been in continuous use ever since (so from around 320 BCE). From an archeological perspective, this continuously used shaft is fairly useless, as almost everything has been destroyed. However, the older shafts were mud-filled, and it is the excavation of these that has revealed information about their mining practices and pork-curing – along with information about textiles, tools, what they ate, how they cooked …

The Romans introduced a new method of salt extraction – by solution. The salt was dissolved into water, the water was moved to salt pans and then evaported and the resulting salt was collected and transported elsewhere for use. This method is still used today.

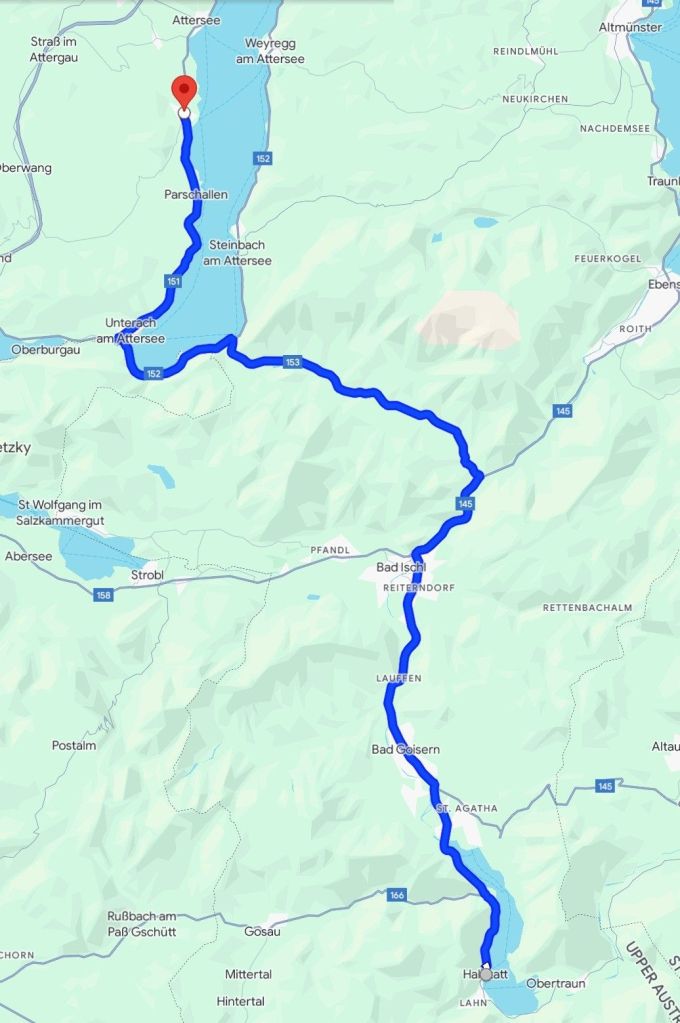

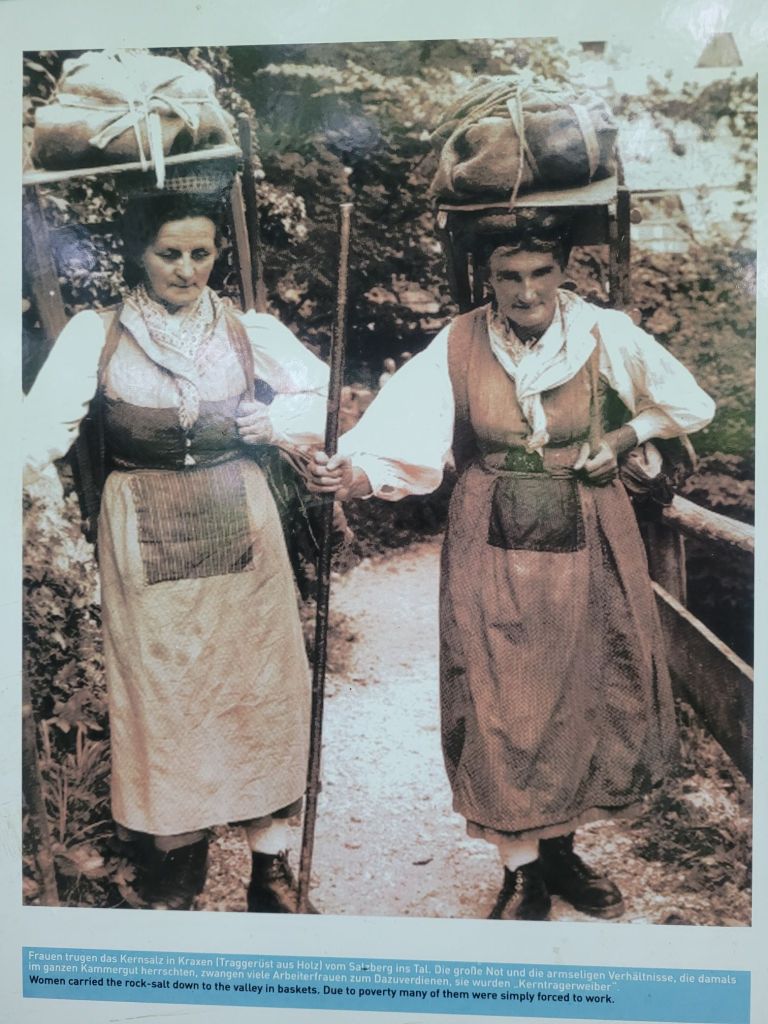

In the medieval period, the pipelines were extended so that the saline solution ran downhill in a series of tunnels and open channels to the boiling pans below. By 1507, the wooden pipeline extended to Ebensee, some 30 km away. Afer being processed there, it was exported via waterways (rivers and lakes). Up until the late 19th century, women used to transport rock salt down the mountainside on rough wooden packpacks. It must have been back-breaking work, as it’s a steep descent (and climb back up).

From being a resource that enabled the local community to live well, the locals working the mines ended up being quite exploited in later years. It was back-breaking work with little regard for for the safety of employees – there was rarely a week that went without at least one death.

Towards the end of the 18th century, tourism in the area started to attract people into the area, with the interest in ‘nature’ motivating people to explore the mountainous region around Halstatt and by 1874 there was a railway to enable their arrival, all keen to enjoy the mountain air. Nowadays, the village is awash with tourists from the far East, who come to explore the village after it featured in a South Korean TV show. Apparently sections have been re-created in China! There were several tour buses parked up, lots of people from a long way away and lots of selfie sticks.

There was almost no-one in the museum.

In 1846, a necropolis was discovered, dating from around 750 BCE, and the finds from this have not only provided valuable insight into a sophisticated life-style (glass from Slovenia, amber from the Baltic, bronze dishes from Italy…) but also given rise to the official name for the people that lived in the area. The ‘Halstatt Culture’ is seen as a distinct people, who worked the salt mines, traded widely and lived well.

The village is known as the ‘Austrian Venice’, as much of it is built on stilts over the water – there is very little flat land around Halstatt.

Above the village, up a funicular railway, you can explore the necropolis, the salt mines themselves and the mountainside (and a cafe with an amazing view point that is overcrowded). The salt mine ‘experience’ is expensive and no-one really wanted to go underground, so we settled for a one-way ride up, expecting a gentle walk downhill.

A good plan, except that the weather closed in.

But up we went.

The rain held off for a while and the views from the top were spectacular, even with the clouds.

Sadly, as we started to walk back down, the heavens opened.

It was wet, wet, wet. At one point we were sloshing down through a constant stream of fast running water that tumbled around our feet.

A quick detour led us to a view of the waterfall above the village – by that time our feet were wet enough that the extra distance made little difference.

While I got extremely wet on the way down, it proved interesting as it revealed one of the problems faced by those living in a village at the foot of a steep mountain: rock falls and avalanches. Protective fencing was in evidence everywhere for both rocks and snow.

Speaking to people in our hotel on the lovely Attersee Lake, they commented on how miserable Halstatt can be. The lake is very deep (therefore dark) and the mountains are very steep and high, so its generally dark when the sun isn’t directly overhead. Especially during winter. And they get a lot of snow.

Interesting what people will put up with to turn a profit (and the salt mines were extremely profitable).