Landing in Chania, we picked up a car and drove towards the far south-western edge of Crete.

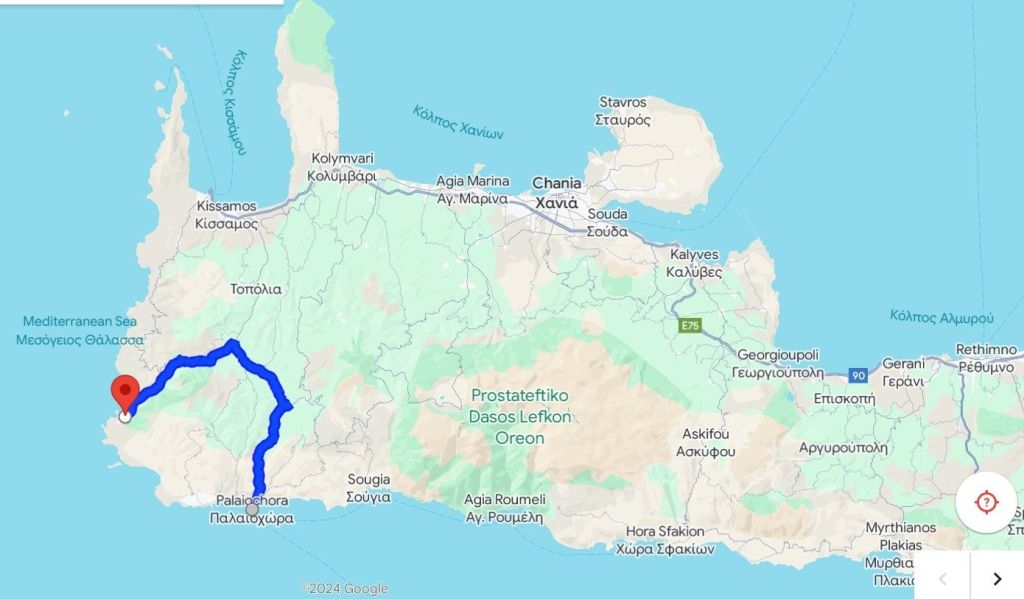

This part of Crete (the western edge of the Chania province) is less well-known (other than Elafonissos), and part of the reason for this is that the routes to the south coast are very compartmentalised – once you get to a particular point on the south coast, there is nowhere else you can go unless you return to the mountains in the middle of the island and take a different valley southwards.

To get to our first hotel – the Glykeria – we followed a well beaten track to that well-known tourist destination Ellfonissos (or Elafonissi – or any other combination of double consonants displayed on the road signs) through the Topolia gorge.

This made for ‘interesting’ driving, as the road is both heavily used by tourist traffic (coaches, cars and motorbikes) and comprises a series of sinuous bends, hairpin corners and blind sharp turns. These are all negotiated on a road which is, nominally, a single lane in both directions, but these lanes are quite narrow and they often reduce to a single-file track, usually when going around a blind corner. Meeting a large coach (or a heavy lorry) coming in the opposite direction requires ingenuity when considering where to place one’s own vehicle – because they give way to no-one and reversing is seldom an option given the queue of traffic behind.

There is nothing like approaching a blind 90 degree turn, with a less-than-useless mirror to help you see round it, only to find yourself confronted by a large coach, driven by a bored looking individual (often with a cigarette hanging out of the corner of their mouths), occupying the whole width of the road as you get to the sharpest – and usually narrowest – angle of the corner. Their skills are immense and I take my hat off to their ability to bulldoze their way past anyone and everything in such large vehicles on such teeny tiny roads. One word of warning however, their vehicles appear to lack a reverse gear as they never move in any direction other than forward.

The number of tavernas with hopeful signs ‘See you on the way back!’ and the string of kiosks selling ‘local honey, olive oil, pollen, royal jelly…’ are testament to the tourist traffic hot-footing down to Elafonissi.

The gorge is spectacular and surprisingly green, with a lot of deciduous trees and pines. At the narrowest – and possibly highest – part the road disappears through a single track tunnel, controlled by a traffic light. Sitting dutifully in front of the red light, we were astonished to see a string of cars pulling past us and heading off down the tunnel. It was dark, extremely narrow (I’m not quite sure just how the coaches manage to squeeze through), and a slightly fraught experience as we raced along trying to keep up with the queue, fearful that those coming the other way would mimic the impatience of those in front us.

Eventually we got over the top and started down the other side, seeing many more olives and fewer other trees.

The Glykeria hotel is a roadside taverna with ten rooms on the opposite side of the road. It’s clean, has nice bathrooms and comfortable beds, a good taverna, wonderfully friendly staff and fantastic views – from both the rooms and the taverna.

Downsides are the busy road (although it is quieter at night) and the coastline is , essentially, rocky, which means easily accessible sea swimming is tricky.

Elafonissi ( a ten minute drive away from the hotel) is, in a word, stunning. Everyone thinks so, that’s why there are so many people there!

After parking in one of the many parking options, the walk to the beaches takes about ten minutes down a rough track heaving with people carting vast quantities of beach supplies – many stopping every few metres to take the obligatory selfie.

The island is separated from the mainland by a shallow channel of water; although fairly easy to wade, the current grew stronger as the wind picked up after mid-day- small children beware. On both sides of the channel the sand is fine, blindingly white (no, not pink, despite its ‘fame’) and soft. The whole area is low-lying, so there is a lot of gently shelving sand – beaches extend on either side of the island.

Crystal clear water, warm, no rocks underfoot… Sounds delicious, and it is, except it’s thigh high water everywhere – and I mean everywhere. So swimming is actually not an option. Floating, wallowing, sitting – yes, definitely – but actually swimming? Not possible. At least in the bits we got to, and we walked most of the island accessible to visitors. It’s a protected environment, so much of the island itself is roped off – and the north side is, well, rocky. But then so is the south side, just less so.

To avoid giving the impression that the tourist board is dishonest about the pink sand, there are pinkish streaks. In places. But unless you are actively looking for them, ‘pink’ isn’t quite the colour I would use to describe the sand.

It was hot, it was pretty, it was packed (and this is out of main tourist season) and the water was lovely. Not one drop of shade and few food outlets (no permanent buildings are allowed in the area). To spend a day would require (in my opinion, humble as it is) a full supply of sun protective equipment, a large cooler of drinks, plentiful picnic food and a few floats. We don’t have enough arms for that.

We also took a drive out to Paleochora, which involved backtracking almost to the single-track tunnel, then going down a different valley system to get to the south coast.

Again, heavily wooded in places but predominantly olives. Many of the olive groves have black nets – or sometimes bright orange, which is a bit of surprise – already spread ready for the olive harvest. It seemed a bit early in the season, but maybe they don’t bother to pack it away and it just stays there all year. In other groves the nets were either coiled around the tree trunk or stretch out in a roll between trees. Either way, the importance of olives was clear.

(In a quick aside, the southwest region of Crete is – so I was told – mainly about the Tsounati olive, which is only grown in Crete and only in this area. It is used for both oil and eating.)

Paleochora is a small town with an old castle (Venetian – ruined), surrounded by the sea: it’s on a spit of land so there is sea on either side. We found the old town charming, full of tourist shops that were a cut above the standard plastic tourist ‘tat’ and lots of eateries. It is busy until the end of October-early November, after which is is apparently dead quiet through the winter months (with only two or three shops open and the same number of restaurants).

The main beach on the west side was fantastic, with a long sandy beach of fine, soft sand, and views out to the open sea. Due to the wind, the waves were quite large and a red flag for swimming was flying. There were a few adventurous souls (mostly men or teenage boys) jumping and attempting to body surf. We settled for paddling and nearly lost our footing a few times due to the strength of the surf.

The church is pretty (not ancient) and very ornate – you can definitely see the Byzantine heritage in the decor.

We ate at a very Greek fish taverna (the Caravella) on the sea front, right next to the harbour, where we popped for a delicious, well-cooked dorade. As usual, despite the restaurant catching their own fish, whole fish are expensive and this was no exception.

It was immensely gratifying to watch a small ferry come in, and notice the open bow doors with passengers standing by the ramp waiting to disembark. They didn’t even moor up, just rested the ramp on the concrete jetty with the ferry drifting sideways as cars drove off.

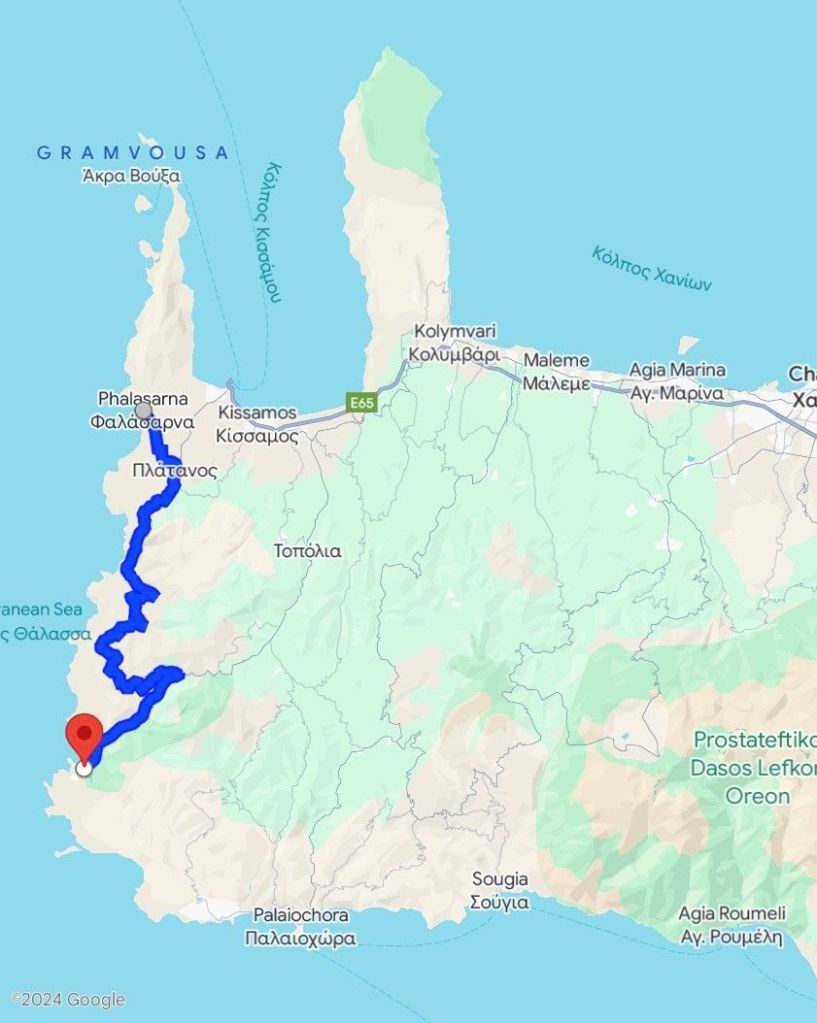

After three nights at the Glykeria we drove up the west coast to Phalasarna – one of the ‘top’ beach areas on the island (and also home to a Minoan site – more of this in a later post).

After driving north up the valley a ways, we turned west and returned to the sea. Large and steep mountains, quite barren, a rocky coastline and a one and a half lane road spinning up and down through tiny villages. While the views were spectacular, the road frequently narrowed to a single track lane, particularly through the villages. This leads to a game of chicken with oncoming traffic. Fortunately we met no buses – although goats and sheep were frequent obstacles.

Unlike the other areas we drove through, there is much less vegetation here and we had definitely lost the big olive groves (although there were a few small ones).

It was a stunning (if tiring) drive, with the sea almost always in view and the islands teasing us through the haze. The road fetches up above Phalasarna, with an incredible view.

The town is strung out both above the beach (right at the top) and by the waterfront. There are many, many, many polytunnels (melons, I think) and olive groves, all around the town. We didn’t find it a particularly attractive place but I suppose people go there for the beach and not much else(well, nothing else!).

The beach is vast, the sand is coarser than it is on the south coast and the waves were boisterous – another red flag for swimming. The northernmost end of the beach is supposedly ‘calmer’; it is also rockier (surprise!). While there is a ribbon of ‘beachfront’ tavernas and cafes, these are all on edge above the beach itself, and the hill to get up and down (at the north end) was quite steep.

Paddling done, we headed for our second hotel, the Milia Mountain Retreat.