Given Crete’s position in the eastern Mediterranean, it’s hardly surprising that its history extends well into the dim and distant past. The presence of Neolithic obsidian tools and blades (obsidian is only found on the Agean islands of Milos, Anti-Paros and Nisyros in the eastern Mediterranean) is testament to Crete’s early connections with the world beyond their shores.

Successive waves of cultures have taken over the island – from mainland Myceneans, to Doric Greeks, to Romans, to Venetians, to Byzantines, to Spanish Moors, back to Byzanatines, Ottoman Turks… not forgetting its more recent history with Nazi Germany during World War 2. Up to 1913 Crete was a separate nation, only becoming right before the First World War and many locals still identify as ‘Cretans’ rather than Greeks (yes, we did ask).

This ebb and flo of incoming peoples has led to some interestingly layered architecture and a fascinating food culture that reflects the myriad of influences.

Of course, due to the mythology surrounding the Minotaur, Crete’s ancient history seems to be better known than its more recent past. And Crete does make much of this fascinating culture, with several excellent museums and a wide variety of sites open for visiting around the island.

The Minoans were named as such by Sir Arthur Evans, the excavator of Knossos (near Heraklion). He didn’t ‘discover’ the remains, that was a Cretan, but he did decide – based on the artwork depicting bulls and the many underground corridors and storage rooms – that he had located the legendary labyrinth and palace of King Minos. He belonged to a series of Victorian adventurers/archeologists (or maybe ‘explorers’ – or even ‘exploiters’) who sought to find hard evidence to root the mythologies of the past in reality. Now I know nothing about archeology and little about ancient history, but I do know that taking Homer as a source of legitimate evidence is possibly not quite as scientific as it could be.

Evans was so desperate to ‘catch up’ with Shliemann, who ‘excavated/discovered’ Troy and Mycaenae, that he saw what he wanted to see when confronted with the complexity of the culture revealed in the stunning beauty of the artwork in Knossos (this includes the pottery). As an aside, yes, there are lots of bulls, but Minoan art also has loads (and loads) of sea creatures, particularly the octopus. But these don’t fit into a convenient myth!

The Minoan civilization lasted for just over 2000 years during the Bronze Age, starting somewhere around 3200 BCE. They are inextricably linked with the story of the Minotaur, defeated by Theseus who, in order to kill him, navigated the labyrinth with the help of King Minos’ daughter Ariadne. There are many versions but the story of the labyrinth was well known across the classical world – there is even a carving of a labyrinth in Pompeii. There is also an awful lot of tosh about the Minoans in popular culture and competing theories about why (and how) they disappeared.

The mystique around the Minoans is partly fuelled by the mythology but also by the sheer age of the civilization. Large palace complexes and other buildings were destroyed by earthquakes, then rebuilt and re-developed, then destroyed again by earthquakes, then suffered fire damage, then were abandoned and/or built over by incoming cultures … Furthermore, of the two scripts used by the Minoans, only one (Linear B) has been deciphered: most of the texts seem to record admin details like how many sheep someone had.

The Minoans (there isn’t much evidence for what they called themselves) traded widely across the eastern Mediterranean, exporting the purple dye from the Murex seasnail (and it may be that they even farmed them intensively according to some) and ceramics (Minoan pots have been found all over the eastern Mediterranean), among other things and they are mentioned as a trading nation in Egyptian texts.

Their interest in visual arts is marked, with painted walls, some with pictures depicting bull-leaping, and their observation of the natural world can be seen in the life-like paintings of birds, fish, squid, bulls… Interestingly, their human figures are much less sophisticated for the most part.

The most beautiful pottery we saw was in the Messara museum (near the south coast), which has a strict ‘no photography’ policy – in contrast to the small (but very nicely laid out) museum in Rethymnon, where the person taking our money urged us to ‘take lots of photographs’.

On this trip we wanted to visit as many Minoan sites as possible alongside whatever else we discovered along the way.

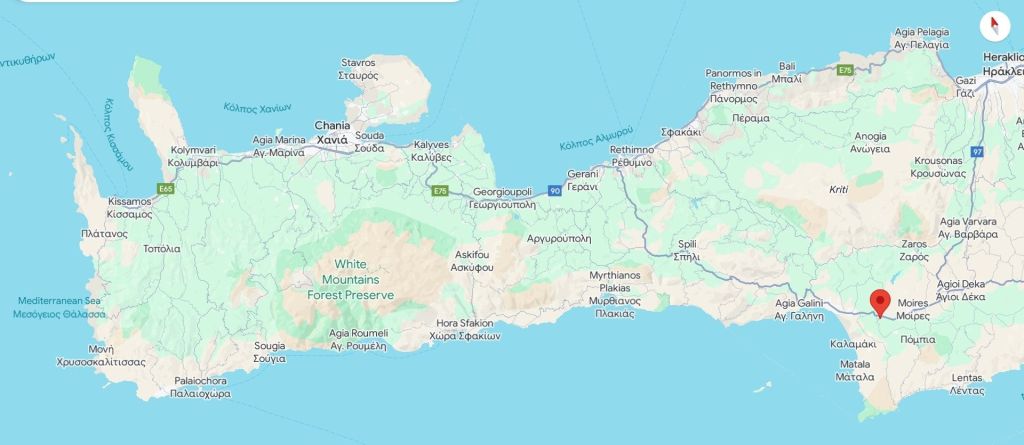

The biggest Minoan site in western Crete is Phaistos, well-known on the tourist trail – which becomes obvious when you see the tour buses parked up outside it.

It’s confusing – just getting that out there – and although there is some signage, it’s a bit the worse for wear (in the hot sun) and not particularly clear. But then everything I have, watched or listened to is equally confusing: there is a lot that simply unknown and there are a lot of competing theories.

Perched above the Messara plain, surrounded by olive groves, there is very little in the way of shade on this site. When I mentioned to one of the attendants (when they stopped shouting at people to get down from the various structures) how hot it was, I was informed that the day was ‘perfect’: apparently it had topped 40C mid-August so our paltry 28C was positively refreshing. I was sweating up a storm.

Phaistos was excavated at around the same time as Knossos, but by an Italian team. Finds included a particularly delicate and fine style of pottery called Kamares ware (after the Kamares cave in the Psiloritis mountain where it may have been made). One significant find was the Phaistos Disk, a ceramic disk with a different spiral pattern of seals embedded on each side. It remains undeciphered. Because of its excellent condition, there were rumours suggesting it was a fake but current scholarship and testing would suggest otherwise. Sadly I have no photos as it was in the ‘no photography’ museum, however T-shirts with a representation of it can be found (Roger now has three).

The area around Phaistos has been inhabited since late Neolithic times (remains from 4500 BCE have been found) and the first palace on the site was built in 1900 BCE. It was rebuilt and re-developed, twice, after two earthquakes, which only adds to the stony jumble. Unlike Knossos it hasn’t been reconstructed, although there are a few places where they have put back steps. But it’s a smaller site than Knossos, with (overall) fewer visitors as it’s further away from the main tourist resort areas.

There are rows and rows of storage rooms (with jars still in them), the standard large central court around which there were various wings, a jumble of buildings elsewhere …

Although it looks as if there weren’t many people, I was just lucky with my timings; there were plenty of people, with many climbing all over things they shouldn’t have been climbing on (the attendants were kept busy).

Phaistos was closer to the coast than it is now due to tectonic activity which raised the level of the land by several meters (up to eight in some areas) and was busy, thriving place until it was destroyed, deliberately, by fire.

Close to Phaistos (a seven minute drive west over the hill and along yet another very narrow road) is Agios Triada, a smaller Minoan palace site. This is much less visited, has no signage whatsoever, is still being excavated and is in a wildly atmospheric location. Like other palace sites it stands on a promontory, surrounded by olive groves and pine trees; originally the sea would have lapped much closer to the bottom of the hill. It takes its name from the village which surrounded it, which was destroyed by the Turks in the late 1800s; the Minoan name of the site is unknown.

There were few people, absolutely no facilities whatsoever (other than someone to charge the entry fee) and it’s small. Despite its small size, some of the most beautiful and important Minoan finds (particularly ceramics) were discovered here: most are in the big museum in Heraklion, some were in the no-photograph musem – so no pictures of finds.

There was a Minoan town next to the palace complex, with what they think was a market-place of small shops.

With glimpses of the sea, the silence only broken by the whisper of the breeze through the pines, and the solitude, it was well worth a visit.

One school of archeologists named the various periods of the Minoan culture by referencing the palaces: Pre-Palatial, Proto-Palatial, Neo-Palatial … And no, these probably aren’t quite in order and yes, there are more of them! Just to add to the confusion, and to the mystique of the Minoans, it isn’t clear what the so-called palaces were for. They all appear to be built on promontories, have a large ‘Great Court’, with small storage rooms and corridors (hence the labyrinth?). But whether they were just palaces where rulers lived or they served an administrative function (the quantity of linear A and B tablets would suggest this) or a religious function – or all three – is not really known.

Certainly the Minoans thought they were important enough to rebuild after earthquakes (a reminder that Phaistos was rebuilt twice) and then important enough to be deliberately destroyed: in 1450 BCE the majority of the palace complexes across Crete were demolished, through what are thought to be deliberately set fires, with the exception of Knossos. Again, there is no evidence yet as to why this destruction happened (and deliberate destruction by fire is also seen in shrines and other religious buildings), just as there is no specific evidence as to how and why the Minoan culture completely disappeared. The appearance of the Mycaeneans on the scene could have been the cause of their disappearance, or the result. Like much of their history, Minoan culture remains a mystery unto the end.

A great deal of effort has been put into bringing this Minoan heritage to the forefront, with very nice museums in the far south (the Messara museum), a lovely new museum in Chania, and a small but well explained museum in Rethymnon: the sites themselves are confusing and more (and better) signage would help. But it’s still thrilling to think that you are walking on paving stones that are over four thousand years old.