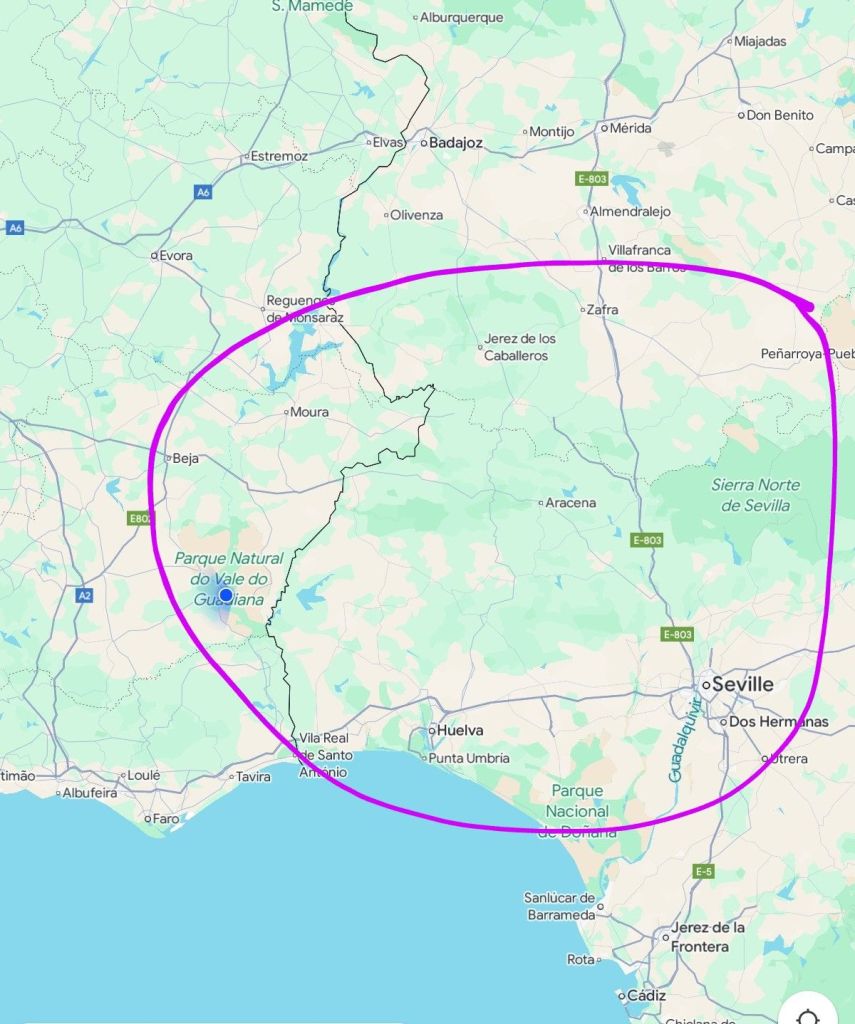

Spain, again you might think, but this time exploring the Guadiana river valley, mostly on the Portuguese side of the border, along with the Sierra de Aracena y Picos de Aroche Natural Park and (hopefully) a few of the medieval castles associated with the Knights of Santiago (competitors of the Knights Templar after the Crusades were over and done with).

Seville airport in the immediate aftermath of biblical storms that ravaged southern Spain, particularly Valencia province, was wet and foggy. Although Valencia bore the brunt of the destruction and deaths, the Càdiz region was also badly affected with flooding in coastal areas and sightings of water spouts and tornados.

The forecast was also not good.

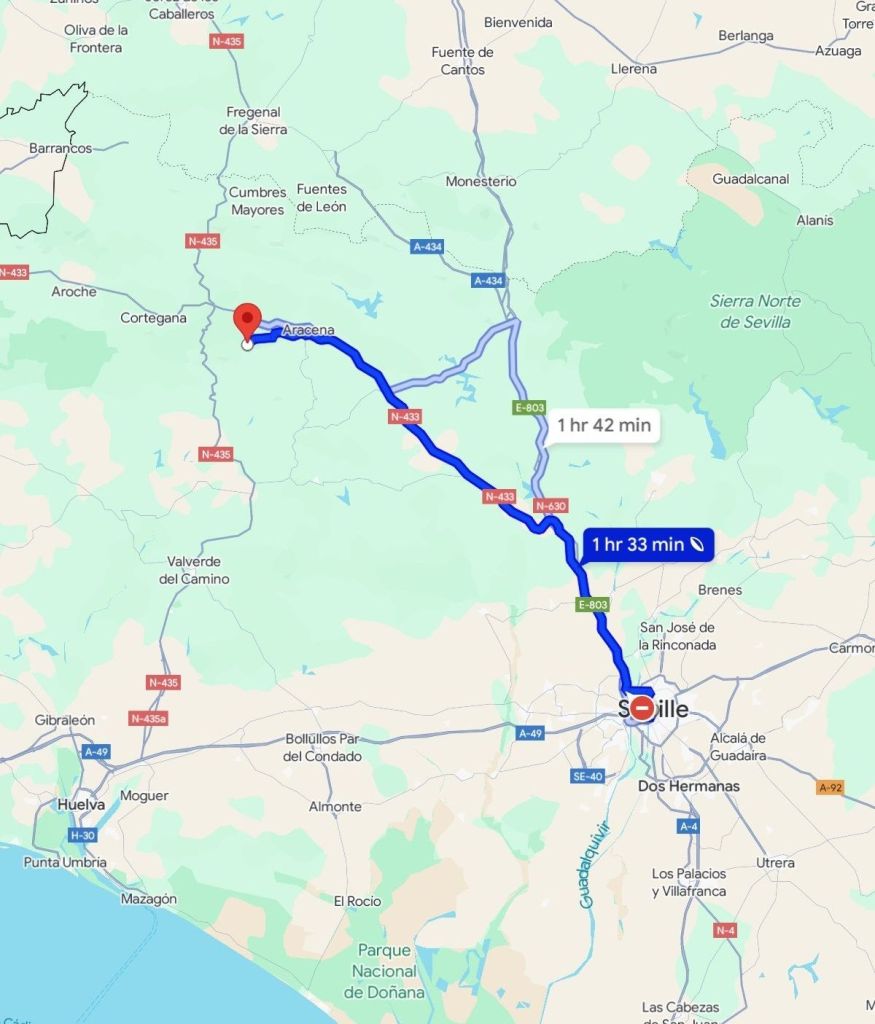

After a night in Carmona (a favourite place in southern Spain, in part for the sheer convenience of access to /from the airport), we headed up to the Sierra Morena, north and west of Seville, to Alájar.

This was a repeat visit to this area. A few days in Aracena, with fabulous late-October weather, a wonderful walk, great food and equally great wine had guaranteed a return trip.

During the planning phase, walking was the main goal: we hadn’t banked on the weather being so grim.

This region is said (by some) to be ‘the most’ deprived in Spain. Having done some digging round on Prof Google, I can’t quite agree to ‘most’. Andalucia IS one of the most deprived (if not THE most) autonomous region of Spain, but the Huelva area isn’t as badly off as places further south in Cadiz province (like Barbate, or Sanlucar de Barrameda). Nonetheless, it’s an area that struggles with employment: agriculture (particularly focused around the Iberian pig) is one main employer.

Production of the emblematic, luxury Jamón Iberico is tightly controlled, with minimum specifications for breed purity, feedstuff and time spent out on the ´dehesa´. To be eligible for the highest quality of ham, the pig must: be a minimum of 75% Iberian breed AND have spent at their final fattening period on the ´dehesa´(this period is called the ‘montanera´), eating only what they find under the holm and cork oaks (ie acorns) with the odd chestnut thrown in for good measure. There is a third oak involved, but I can’t quite remember what it’s called – mostly it’s cork and holm.

It seems as if every town or village you drive through in this area has a ‘secadero’ or drying factory.

Another product much in evidence in this area is cork; the hills are dotted with evidence of cork harvesting. Every fifteen years or so the bottom half of the trunk is stripped of bark, leaving a bright orange splash of colour which quickly darkens, regenerating slowly until the next stripping session. Shops sell a lot of ‘stuff’ made of cork – it’s almost as ubiquitous as the pig products.

The villages in this area are referred to as ‘white villages’ and many show signs of a Moorish past. Rows of white houses, no prominent main square and the church often tucked away down a side-street. It’s all pretty but looks much nicer in the sun.

A word about the street paving. The importance of tourism and, therefore, appearance, has led local communities to use pseudo-cobbles on their streets. While it looks lovely (really, it does), it’s problematic because it’s laid on an impermeable base which may lead to lower maintenance costs, but results in much greater water run-off during the rainy season. This was a topic of conversation at our B and B in Alájar, given the coastal flooding when rising tides met hugely increased water runoff from the mountains.

Even more attractive is the practice of adding a permanent welome mat in stone outside your front door. A practice seen in several villages in the area, most famously in Linares de la Sierra.

Thankfully the weather improved for our last day and we took a spectacular walk to the neighbouring village of Linares de la Sierra (and back). It was only about 10K, but there were enough ups and downs (and slightly water-logged downs) to keep it interesting.

We saw plenty of pigs, lots of oaks (of various types), flowering ivy covered in wild bees (the noise was incredible) and trees covered in lichen (which demonstrated how clean the air was).

As we came towards Alájar on the final leg, we had a wonderful view – which made up for the two days of cloud and rain.

Perched above the village is the Peña Arias Montano, with a fabulous viewpoint, a small church (they refer to it as a hermitage) and yet more walks. Much money has been spent in this area to develop hiking and biking trails and they are very well signposted – although their maps are nowhere near as good as those published by the UK’s Ordinance Survey.

From the Peña you can see layers of mountains towards the south. If the weather is really clear, and the sun in is in the right place, apparently you can see, right at the very top, a silvery strip of sea in the distance. This is also a dark sky area, they have even installed a special stand for ‘star selfies’ – too overcast for us, unfortunately.

Our stay in Alájar was only slightly marred by the rain (there’s very little to do if you can’t get outside). We stayed at Posada San Marco, which calls itself a hotel but is, in actual fact, a B and B. The food was generally good (a lot of pork was involved) and everyone was incredibly friendly. Although Alájar is on the remote side, it’s clearly on the Spanish tourist trail, as there were several rural hotels, rural rooms, and rental properties advertised around the village.

Peaceful, beautiful, welcoming and plenty of stunning walking (hilly, you have been warned). We will return.