For years (and years) Spain completely ignored its Moorish past, which is short-sighted given the nearly 800 years the Moors spent in El-Andalus, the significant donations of Arabic words to the Spanish language, the influence on agriculture, food, architecture… the list seems almost endless. Thankfully, southern Spain has woken up to and acknowledged its Arabic past – even celebrating it in places; Portugal is less successful in doing this, possibly because so much of the Moorish influence has been lost (for whatever reason). In this, Mertola is an anomaly: it appears to be one of the very few places in Portugal where significant Moorish influence is not only present but has been excavated (is still being excavated) and celebrated.

For Mertola, history is a big tourist draw. Its museum of Mertola is, it could be said, distributed across multiple small sites. No one site is particularly significant, but taken together (and they can all be seen in a day), they reveal the changing layers of history and culture from the Roman period right through to the 20th century.

And, of course, the 14th century castle that dominates the town shouts ‘get your history fix here’.

In Roman times, Mertola’s footprint was almost as large (if not larger) than its modern day area – which is considerably larger than its Moorish or medieval size. The town has gone to great pains during recent developments to excavate, maintain and display archeological remains, so the town hall now houses the remains of a Roman house in its basement, while the Museo hotel is built over a 12th century house from the Almohad period (although it may have been Christian, or not – the jury is out).

The town clusters around the castle, originally the site of a Moorish fortification which itself was built adjacent to (and partly over) the remains of Roman and Visigothic administrative buildings (and probably some fortifications but these aren’t mentioned). When the Knights of Santiago de Espada (the Knights of the Sword of Saint James) took Mertola from the Moors in 1238, the castle was rebuilt and extended to become the national headquarters for this military arm of the regligious order.

A criticism of the museum of Mertola is that the signage in the castle (particularly in the exhibition areas) is only in Portuguese, which isn’t conducive to engagement for those not conversant with the language (elsewhere there is English as well as Portuguese).

Immediately outside the castle gates is a recent statue to the Moorish leader Ibn Qasi, described as ‘Senhor de Mertola’ between 1144 and 1147.

While this appears wonderfully enlightened and tolerant, upon research it becomes apparent that Ibn Qasi was a revolutionary insurgent who rebelled against the Almovid rulers, then changed sides, then was beheaded by his own followers. It’s all a bit murky – some sources claim he was an early Christian who converted to Islam – and it’s not really clear why he might be recognised in this way.

Also in front of the castle, constructed over what was the Roman forum, are the remains of early Christian buildings – a bishop’s palace, at least two baptistries and a burial ground. These were Aryan Christians, so probably Visigoths, although this term isn’t used anywhere and (again) it isn’t clear why. The remains of mosaics are unusual for Visigoths as they contain human figures – the Visigoths tended to stick to plant and floral motifs (although this idea could just be based on what survives, which isn’t a lot, rather than ‘fact’).

Immediately next to (and over, in places) what are called ‘proto-Christian’ remains (ie Visigothic) are the remains of a large number of small Moorish houses. The signage takes great pains to point out the drainage (sewers to you and me), commenting that it was very unlike what was happening in the rest of Christian Europe (there is a sense of a comparison in favour of the Moors). At one end a small Moorish house is reconstructed, remarkable for it’s tiny size and indoor toilet area (no, no running water, but jugs to wash in and a latrine that disgorged into a sewer).

Constructed around a small patio with a small growing space or water collection area, the house comprised storage facilities, a cooking area and a few small rooms; it was hard to see how women could possibly have spent much time inside, given how small the rooms were.

Adjacent to what was the Forum a Roman temple stood, later built over with a Visigothic church which was in turn built over by Moors when they constructed a mosque. After Mertola was taken over by the Knights of Santiago, the mosque was converted into a Christian (Catholic) church, still in use today. The mihrab has been revealed behind the altar and the interior columns echo those of other mesquitas across the southern Iberian peninsula.

Underneath the church/mosque is a small museum highlighting the Visigothic foundations. Not much has remained of the Roman temple.

Mertola’s importance as a river port is seen in the remains of a Roman jetty, which is enormous, used both for loading and unloading and also defence against hostile river traffic. The water level has dropped in the river due to damming further upriver, so it is tricky to see just how this structure would have worked.

The Mertola museum does not, however, just focus on earlier history. It also tries to present life in more recent life in this small, remote town that must have suffered economically when the river traffic and mining dried up. There is a blacksmith – the last occupant retired from the business in the 1970s and a miniscule house that was occupied by a family of five until the 1970s.

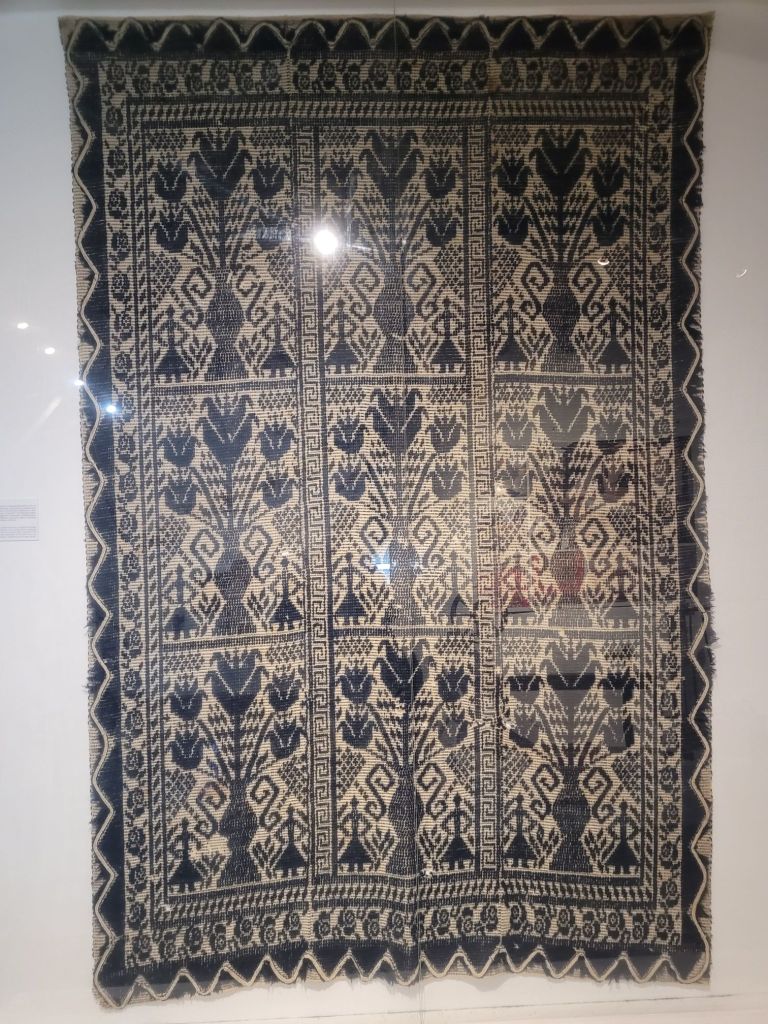

In the weaving co-operative, older women from the town demonstrate an age-old craft, trying to maintain a cultural link to the past. They are quite jealous of their designs, so one lady unwrapped a large blanket which she had woven herself, telling me (in French!) that it was kept wrapped as people had taken pictures and stolen her designs. It was beautiful, using an indigo dyed wool that is a speciality of the area. The ladies copied a very old rug rescued from a local church. The original hangs in the museum, the copy hangs in the church.

Further afield, in Minos de Sao Domingos, there is a miner’s cottage (we didn’t visit that) but it’s there.

Not one of these individual museums is large or particularly detailed. But taken together, a lasting impression is built up of a town that was full of importance in early history and is now taking steps to not only preserve this past (both ancient and more recent) but to use it to redefine itself in the future.

Mertola was an enjoyable place to stay: the museum is interesting, the town is pretty, there are some decent places to eat and some fantastic walks. The tourist office has a collection of walk maps which they hand out free of charge and all the museums are free.

The feral cats are well fed and many have been taken in to be neutered (the tip of the left ear is missing if they’ve been ‘done’). This is hugely civilized.

Behind high walls, life goes on much as it did in the past – on one street olives machine gunned down onto a large plastic sheet spread over the road. Above, an arm bearing a stick emerged occasionally, vigorously beating the branches that overhung the wall.

The streets are steep in places and there are lots of stairs. But we felt it was worth it.