Facing the cathedral, are the statues (cast-iron maybe) of eight dogs, four on either side of Santa Ana square. These sit or lie, alert for a command that will never come, as taxis and delivery vehicles clop, tinkle and chink their way slowly over the loose cobbles in front of them while children ride and pat them.

These Canarian dogs could represent those dogs that the Guanches people brought with them from Africa, or the dogs that guarded the city: no-one really knows. Pliny the Elder claimed to have heard from an African king that the island was named for the many dogs on the island that the Guanches people revered and mummified – ‘can’ being the word for dog (Latin, however).

This all suggests a lot of dogs.

Provenance – a gift to the major from a literary personage or a grateful French sea captain or someone else – is as unclear as what they represent and a quick Google search only serves to muddy the waters further.

What can be said, however, is that archeologists haven’t found any significant traces of dog remains in their excavations. So the whole Guanches theory of dog worship (as mentioned by Pliny the Elder) is shaky.

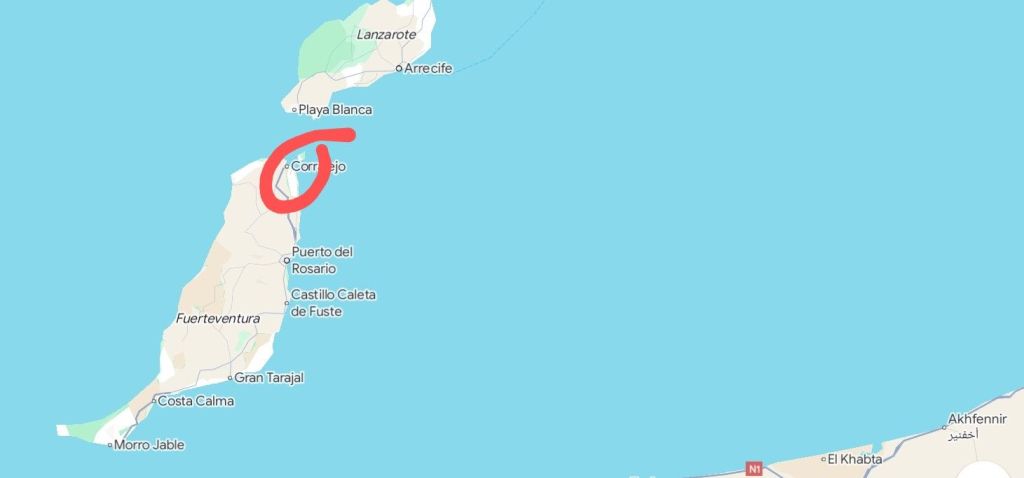

Greeks and Phoenicians knew about the islands but there is no evidence that they visited. Romans did, setting up a small factory to process the purple dye from the murex mollusc. The Romans set up shop for a short period of time on an islet that was home to sea lions – called ‘Lobos de Mar’ (sea-wolves) in Spanish. It isn’t too far a jump to get to ‘dogs’ from ‘wolves’ – or ‘can’ from ‘lobos’ – and thus to ‘Canaria’. The islet, by the way, is still called Isleta de Lobos and is between Fuerteventura and Lanzarote (and quite close to the African coast).

Evidence suggests that the Guanches people started to arrive in the islands from Africa in the fifth century BCE, bringing their livestock and seeds with them. The arrival of the Spanish wiped out their culture, their language and almost all of their people. We visited the museum of the Canaries (which is dedicated to the Guanches) and two archeological sites linked to the Guanches people.

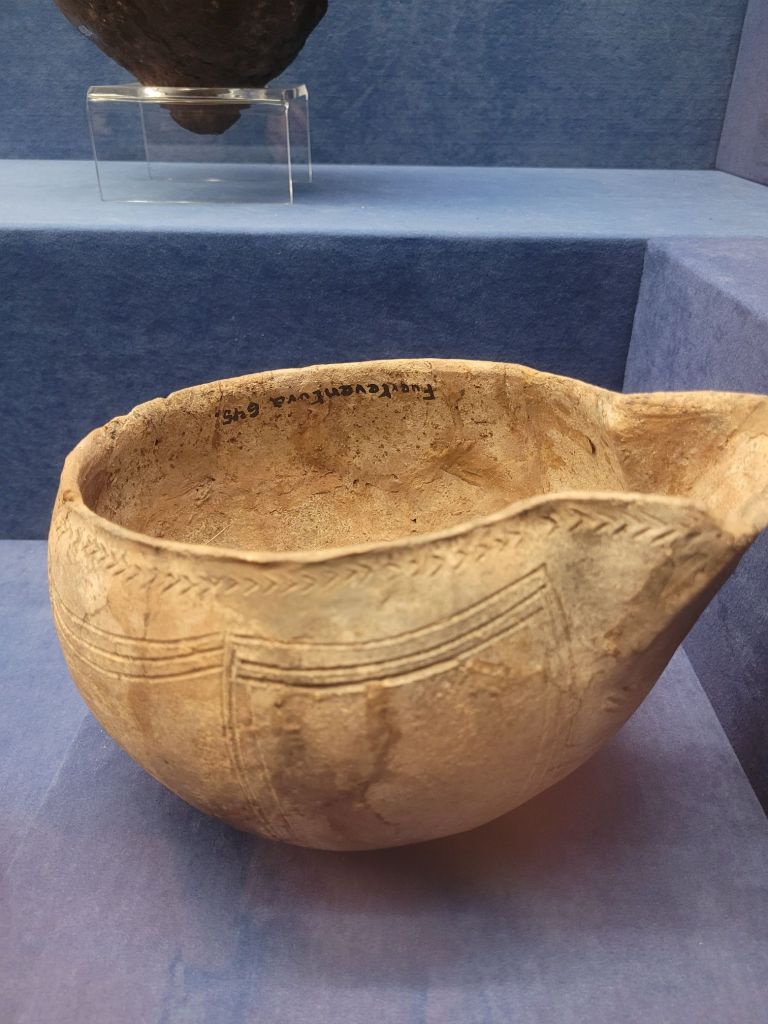

The museum (in Las Palma) is extensive and although the many pots and tools weren’t that entrancing, some of the information provided was definitely worth the time.

The Guanches, genetically linked to the Berber tribes in North Africa, planned and built their villages and town with a view to longevity, decorated their buildings and religious areas, produced decorated pots of many shapes and used a variety of weaving and stitching techniques to produce baskets, rope, hides, clothing…

They lived in caves, excavated from the volcanic tuffa by hand, or in houses built below ground with small walls providing a roof, although there were some buildings fully above ground.

Dwelling places were seen as generational, with subsequent generations taking over from the previous one, and there was a significant degree of town planning involved. In the National Park, the cave dwellings are almost small towns built into the rocks on three levels, with extensive living space and storage areas. Many are not obviously accessible, which begs the question of how they managed to get into their homes.

They cultivated wheat, barley, figs, lentils and white beans, moving their goats and sheep from pasture to pasture according to the time of year. There was no writing (that is known of) and there are no accounts of the Spanish invasion from the perspective of the Guanches people.

The museum also houses what appears to be a superfluous collection of bones and whole skeletons belonging to the Guanches people. The time taken for the picture represents about the amount of time it took to walk through it staring at the floor. Several graves (with whole skeletons) are also displayed. This disturbing of the dead has always made us slightly uneasy.

After picking up a car we drove to Galdar, site of one of the largest and most important Guanches settlements (often called the ‘capital city’ of the Guanches people).

It has a pretty square surrounded by colourful buildings, an unremarkable church (placed almost perfectly atop the Guanches religious site) and an impressive (and accidental) find of enormous importance.

Just beyond the main square were banana planations (initially nopal cactus fields, for the cochineal beatles) in terraces down a hillside. In the second half of the 19th century a plantation worker fell through a hole and into a decorated room that contained mummies. After a number of years, the room was excavated and during the process of excavation, several more sections of the terrace collapsed into further buildings. What was eventually discovered is a large number of houses, with one painted tomb housing mummies, and a wealth of artifacts dating from around 300 CE until the Spanish conquest of the island – at the latest count over two million.

The painted room was fully decorated, including the ceiling, with geometric shapes and varying colours all based on local minerals – no blue or green. There was no documentation for the original incursions into the tomb, so no record exists of what was found. Evidence for multiple mummies comes from the use of the plural in the original newspaper report of the discovery. Essentially no one really knows exactly what was in there originally as it had been plundered by the time it was excavated.

Once the tomb opened for visitors, within 10 years almost 50% of the painting was lost. It’s now shown through a perpex ‘bubble’ and no photography is allowed. There is, however, a copy in the museum.

After Galdar we drove up into the Tejeda National Park, where we stayed on the southern rim, looking north into the caldera and across to the sea.

This area was widely populated by the Guanches, with multiple sites dotted around the various valleys and ridges. One of the most important is Roque Bentayga, of spiritual importance to the Guanches and also the place of their last stand against the Spanish.

The small ‘thumb’ that sticks up just beyond the larger rock was the centre of the Guanches’ astronomy and spiritual life, while a large number of tombs (Cueva Reyes) are cut into the rock just along the ridge. It’s no wonder they defended it fiercely.

That the Guanches people existed is in no doubt. What is shocking is the number of questions that still exist about them. There is still no answer (or even theory) as to how they arrived in the Canary Islands: the Berber people they derived from had no maritime experience or culture. Nor is there any indication as to how much connection there was between the various islands in the archipelago – despite being able to see Mount Teide on Tenerife from the Tejeda National Park.

There was a startling picture in the Canary Museum of a family living in less than ideal circumstances, immediately next to a display about the living conditions of the Guanches. What was startling was that there were people living in similar conditions at the time when photography was available – the implications are that they were probably descendants of the original Guanches people.

It is also only in the last 30 years that any archeological investigation of Guanches sites have been done with rigour and documentation.

But it’s a Good Thing that these mysterious people are now coming into their own.