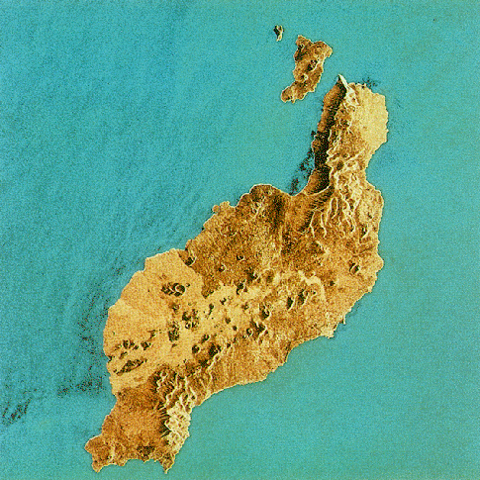

Second oldest of the Canary archipelago, Lanzarote is also (according to much of what I have read) considered the most volcanic, with several volcanoes that have erupted over a long period of time and produced the most volcanic material. There are at least four large calderas, numerous cones and vents, and extensive lava structures (fields, tubes, caves…).

Looking at satellite maps (with apologies for the virulence of the colours) and the Google terrain map, you can see just how many little cone shapes march in parallel south-west to north-east.

Once again, researching the volcanic history of the island is made tricky by the wild swing between ‘it was volcanic’ to tracts filled with specialist vocabulary that makes little sense to me – eg ‘subaerial period’ or ‘complex tabular sequence’.

So with the proviso that anything I write is a vast simplification, I will sum up with: there were a lot of volcanos, there were several huge and lengthy eruptions, the volcanoes appear to be either extinct or dormant.

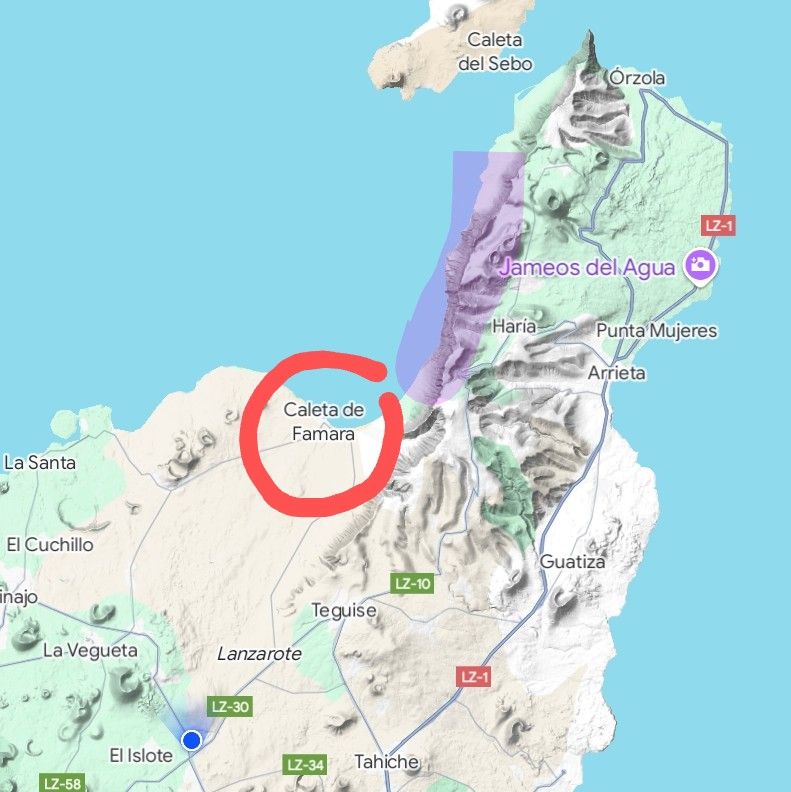

Because it’s had such a long time to erode, Lanzarote’s highest peak isn’t even as high as Fuerteventura’s – just shy of 700 metre – and there is a lot of flat-ish land. But signs of previous volcanic activity are everywhere. Towards the north of the island, the Famara massif rises up to 500 metres above Caleta de Famara, just opposite La Graciosa.

The beach and bay are the remains of the ten kilometer caldera of a massive volcano centred around the island of La Graciosa. The cliffs that rise up behind beach towards the east are what remains of its eastern flank. Volcan de la Corona, further north and east of the Famara cliffs, last exploded 25000 years ago.

This eruption left lava over a large part of the northeast of the island forming several large lava tubes, one of which extends longer than seven and a half kilometres, of which at least 1.5 kilometres lie under the Atlantic. Two big tourist attractions – Cuevas Verdes and Jameos del Agua – resulted from these formations (more of the Jameos del Agua in a later post).

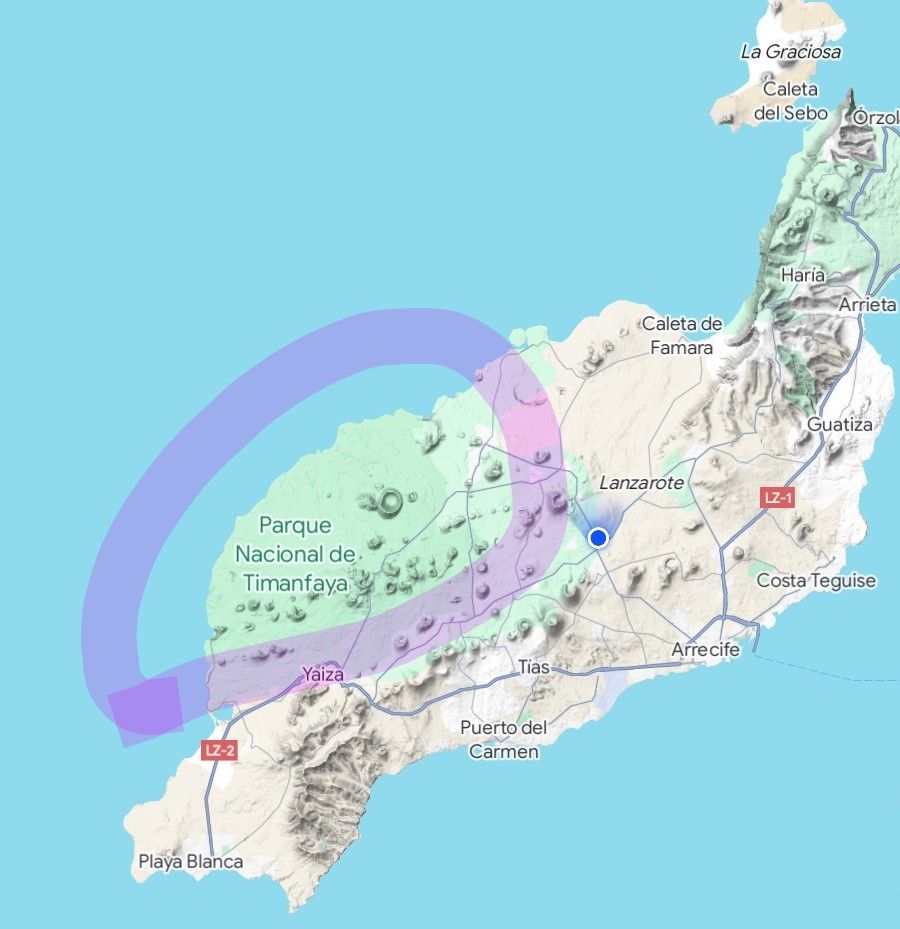

Several of the volcanic events on the island have resulted from something called fissure eruptions, leaving a ‘line’ of cones – on the satellite maps above, two parallel lines can be clearly seen. It’s quite odd to see them ‘in the flesh’, one cone after another. The most recent ‘fissure event’ was in the mid-18th century – so just under 300 years ago – the Timanfaya eruption.

This happened across six years, destroyed a large portion of the land being used to farm cacti for the cocchineal beetle, swallowed a few villages and left moving eye-witness accounts of the events.

The whole area is now either the Timanfaya National Park or the Parque National de Los Volcanes. The Timanfaya park is truly incredible. The only way to visit is to either walk, or to park up and take a bus tour. It’s not inexpensive but it’s worth it – although some of the twists, hairpin bends and knife edge dykes that the route follows caused concern in those of us worried by heights. Pictures cannot do it justice.

Everyone on the bus gasps and oohs almost in unison, leaning over from side to side, getting close up and personal while desperate to catch ‘that’ picture. While the bus will stop in particular places, and the driver might open the door to allow photos to be taken avoiding the glass, you are not allowed to alight from the bus. Several people tried. Once.

There is smooth lava, rough lava, lava tubes, ash, lumpy lava, ropey lava: every type of lava you could possibly imagine, most of which I couldn’t adequately photograph.

At the end of the route, back in the car park, there is a demonstration of how close to the surface the volcanic activity continues to be – at a depth of 13 metres, the temperature is 600 centigrade. They do a lovely demonstration pouring water down a tube, counting down two seconds and then watching the tourists jump as steam geysers out of the tube with a thump. The restaurant there will be covered in a later post on Cesar Manrique (along with the Jameos de Agua and other stuff).

During the eruption, lava poured inexorably south-west where it met the Atlantic, forming impressive black lava cliffs confronted by foaming waves.

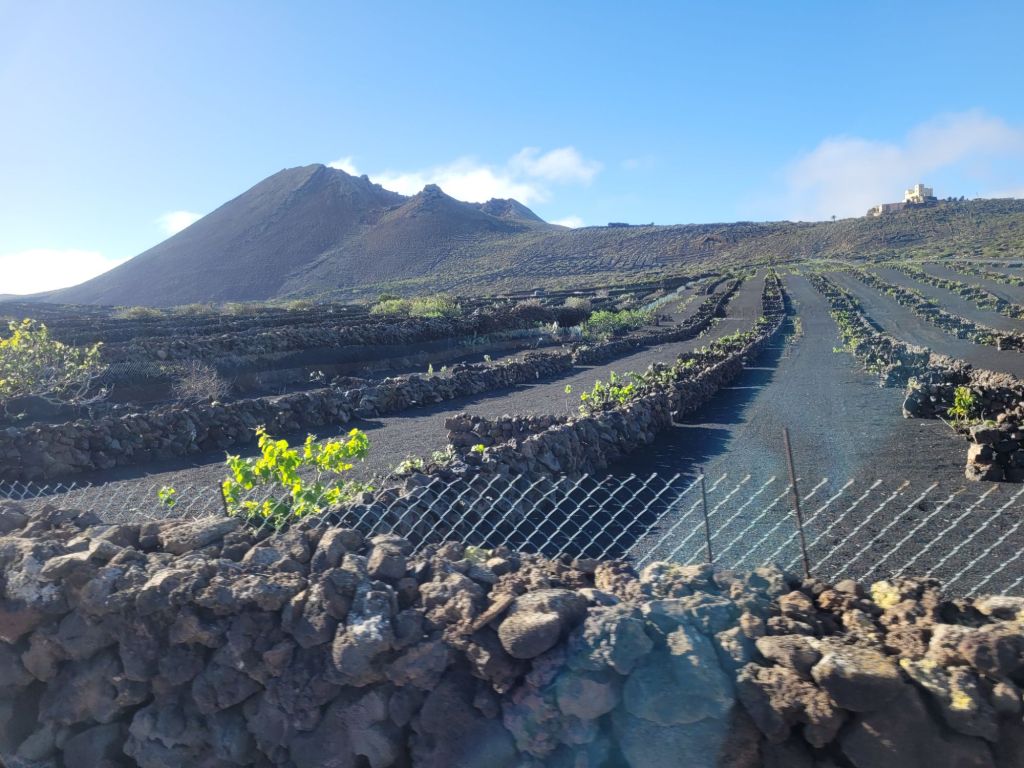

While this eruption (and the final phase of activity in the early 19th century) destroyed a significant portion of the fertile land on the island, it left an enormous quantity of highly fertile lava ash which was exploited for crops; the ash retains moisture so after planting, a healthy layer is spread around to conserve water, regardless of how it is delivered. Mostly it’s vines, lots of them. There are vineyards all over the island, and we didn’t see one that wasn’t on black lava ash.

Most noteworthy is the wide range of constructions used to protect the vines from wind – either the cool winds blowing from the north-east, or the hot winds blowing from the Sahara, just east of the island.

There are cones, dug into the sand, with plants at the bottom; some have a few layers of stones in one arc of the hole. Sometimes there is no hole, but a slightly large wall of lava stones arcing around a plant, with layer after layer arrayed up a hillside. Other times there are larger, rectangular fields with a serrated stubby ‘zip’ of short walls forming small cubicles containing one or two vines around the edge of the field. Sometimes it’s a long thin corridor, with walls on either side and a single column of plants marching along the centre. Sometimes it’s just rows of short walls. It seems to depend on the gradient of the hill, the direction faced and the most frequent wind direction. It might also depend on the grape type (this is a wild guess). Lanzerote escaped the phylloxera infestation so most of its varieties are old; wine production is an important industry and there are many different bodegas, all offering tours and tastings. The whites were minerally, dry and flavoursome, pairing perfectly with the fabulous fish we ate: we preferred them over the red, although we only tried one of those.

Wherever you are on the island, volcanoes are in your face in some way, shape or form – on the horizon, in the rough ground, in the broken crust shapes, in the ash.

The island continues to exploit its volcanic resources in any way it can.