Founded in 43 BCE, Lyon became an enormous conurbation, capital of the Roman province of Gaul. A theatre, amphitheatre, circus and even an odeon (for music) reflect a large population that needed varied entertainment in an important city. Situated as it is, between several hills with limited flat land beside the two rivers, the constant need for living space meant that Lyon’s ‘Roman-ness’ was well known, with excavations and collections dating back to the late 18th century.

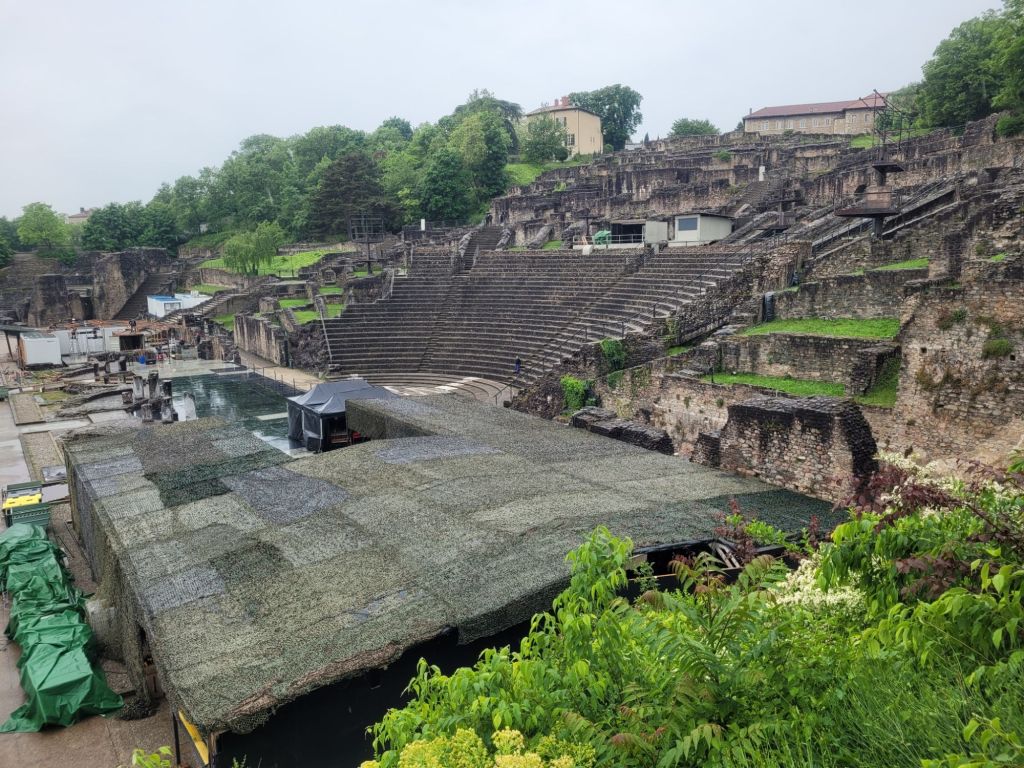

The Gallo-Romano museum in Lyon has been built adjacent to the theater and odeon – excavations are still ongoing. They can be seen from large windows on every level and there is an exit directly onto the site.

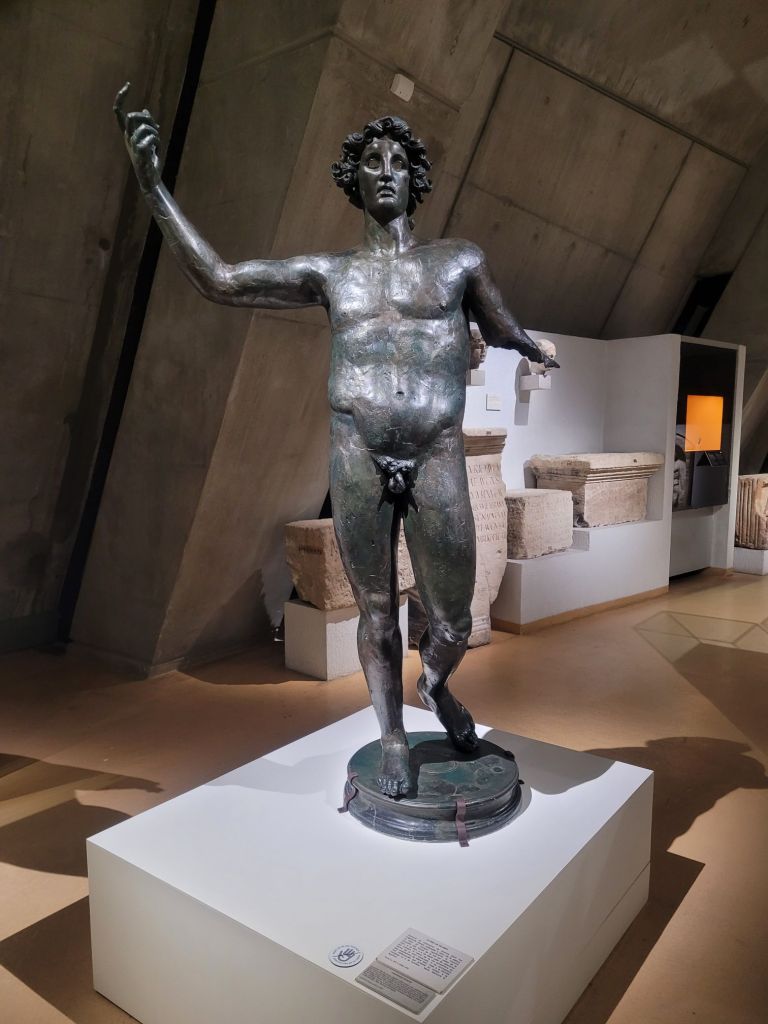

Pre-Roman history is covered briefly through a few cases full of bone, antler, stone and flint tools (not many flint ones) which are swiftly followed by some astonishing finds from the Gaulish tribe that lived in the Vaise plain by the river Saone (in the northern section of modern Lyon).. The bronze work is incredible and reveals a sophisticated culture that had trading contacts with the Romans (apparently they enjoyed Italian wine – who doesn’t?).

The remains of the chariot are the most complete example of its type. The calendar in the middle is interesting because it’s Gaulish but is inscribed using Latin script: its also huge. The figure is thought to be a Gaulish god. All three would have required considerable skill and expertise – so much for the Romans being a civilizing force. After three or four large display cases, it’s on to the Roman remains.

There are lots and lots of funerary stones and monuments, lots of Roman pots, busts, torsos – the usual stuff you find in museum dedicated to Roman ‘things’. Sadly the signage is mostly in French, so it was all a bit opaque at times.

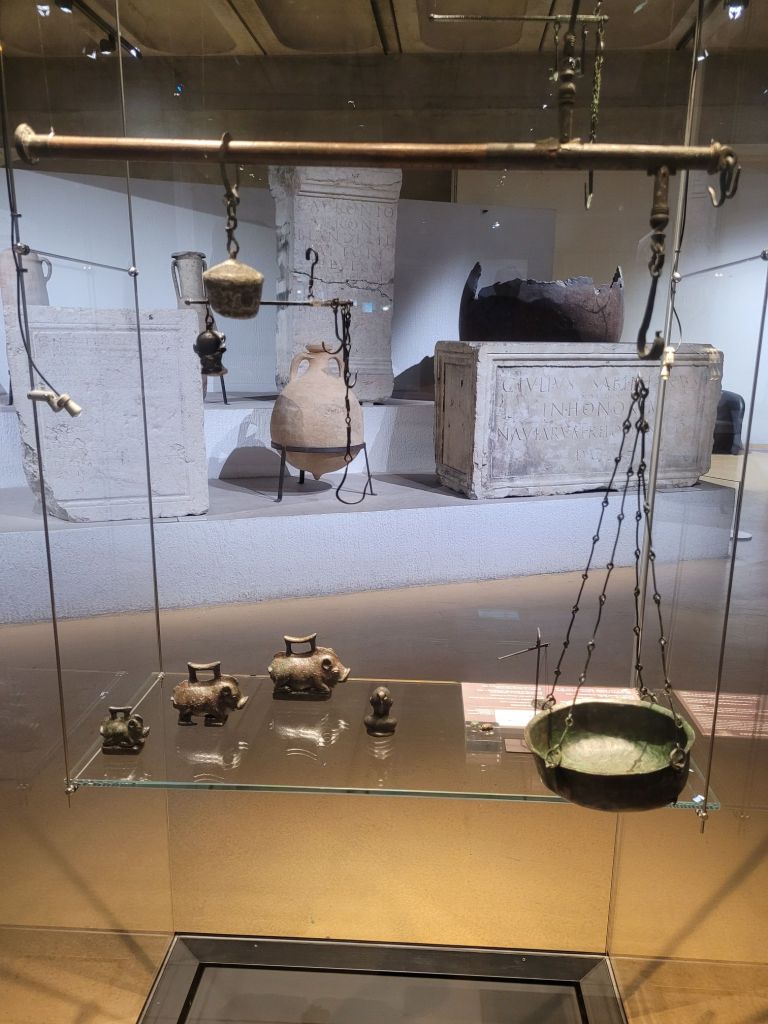

Among the jumble of stone and pottery, there are several very nicely presented displays of equipment for trade (measuring scales and the like), jewellery and glass.

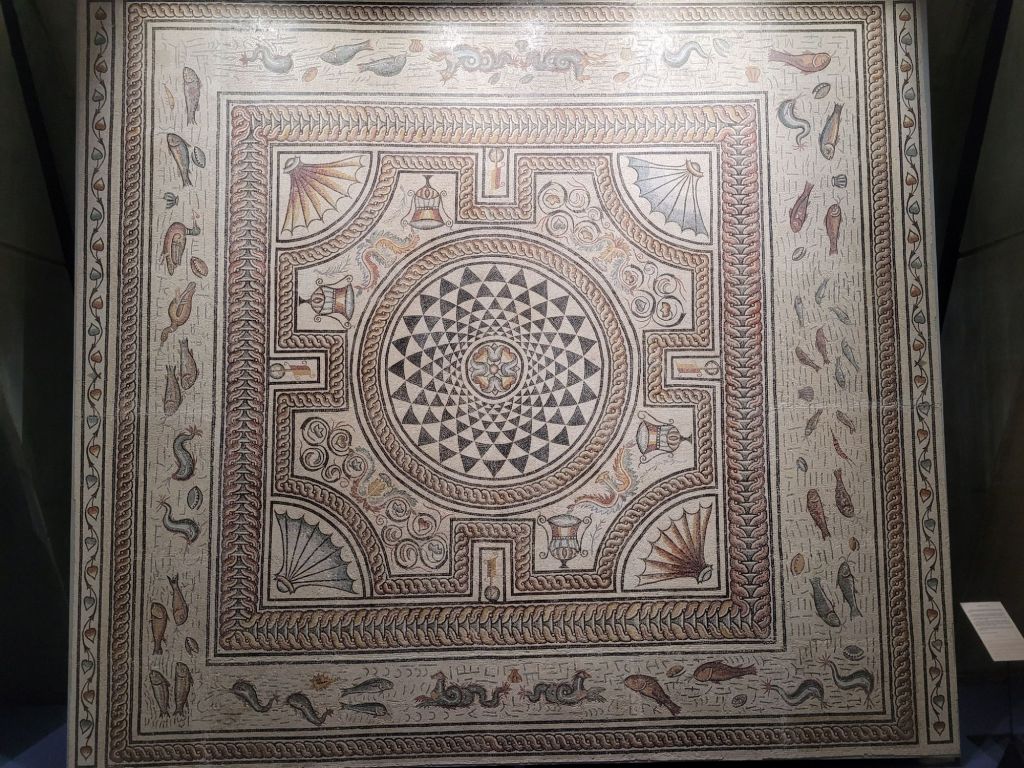

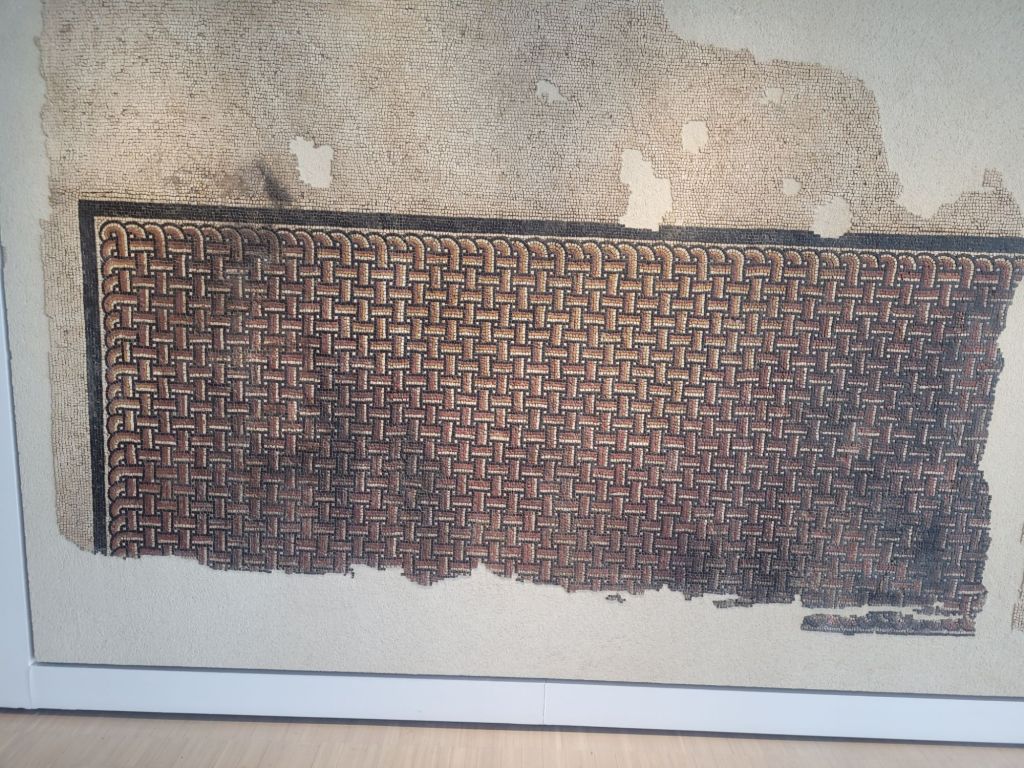

The mosaics are beautiful with several having viewing galleries from above. While this seems like a good idea, in actual fact the mosaics are too far away to gain anything more than a general overview and often the glare is obstructive.

It’s an impressive building (all 1970s monumental concrete and glass) but somehow the displays and the story told through the museum feel dated: it’s all about individual pieces. In terms of new information, there wasn’t much other than the suprising skill of the Gauls in bronze work.

A caveat to this was the fascinating exhibition on the bottom floor which explores the lives of six Roman denizens of Lugundum who came from disparate parts of the Empire: western France, Germany, Rome, northern Turkey, Syria and north Africa. Three women and three men are revealed through their funerary monuments, fleshed out by contextual knowledge about others who led similar lives. Sadly it’s a temporary exhibit – they should make it permanent.

Vienne, which is 35 Km downriver, was surprising. It’s an 18 minute ride from Lyon Part-Dieu, along the river (and the motorway) through a mostly built-up landscape to a small town that houses some interesting remains. This pretty old town has a fairly complete temple right in the middle, one of only two in France (the other being the Maison Carree in Nimes, which is better preserved) and a large theatre on the hillside in the upper part of town. Other than these, Vienne was thought to be mostly Roman farms with the odd large villa: from the 17th century occasional finds were uncovered in fields or under gardens.

However, in the mid 1960s, a new secondary school site was chosen and, once development had started, an extensive Roman town was uncovered. Excavation of this site (the school was relocated) and further excavation around the town has led to a re-evaluation of Vienne. More importantly, because the area hadn’t already been ‘excavated’ (read plundered) by Victorian ‘archeologists’, a more considered approach has revealed an important trading hub.

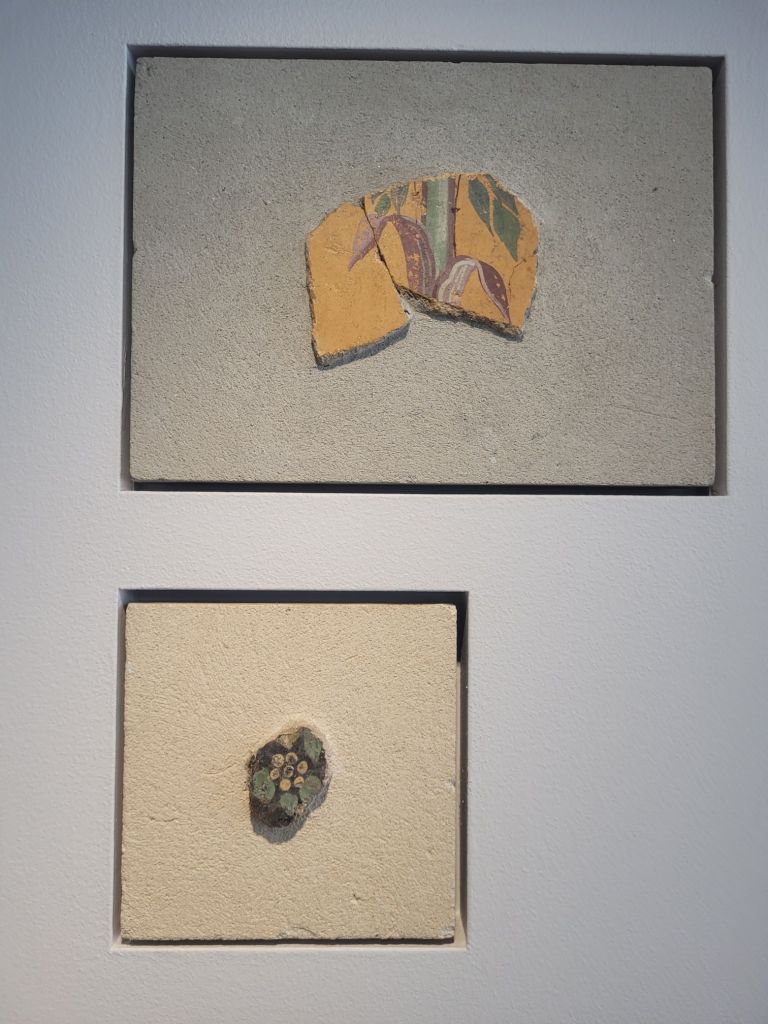

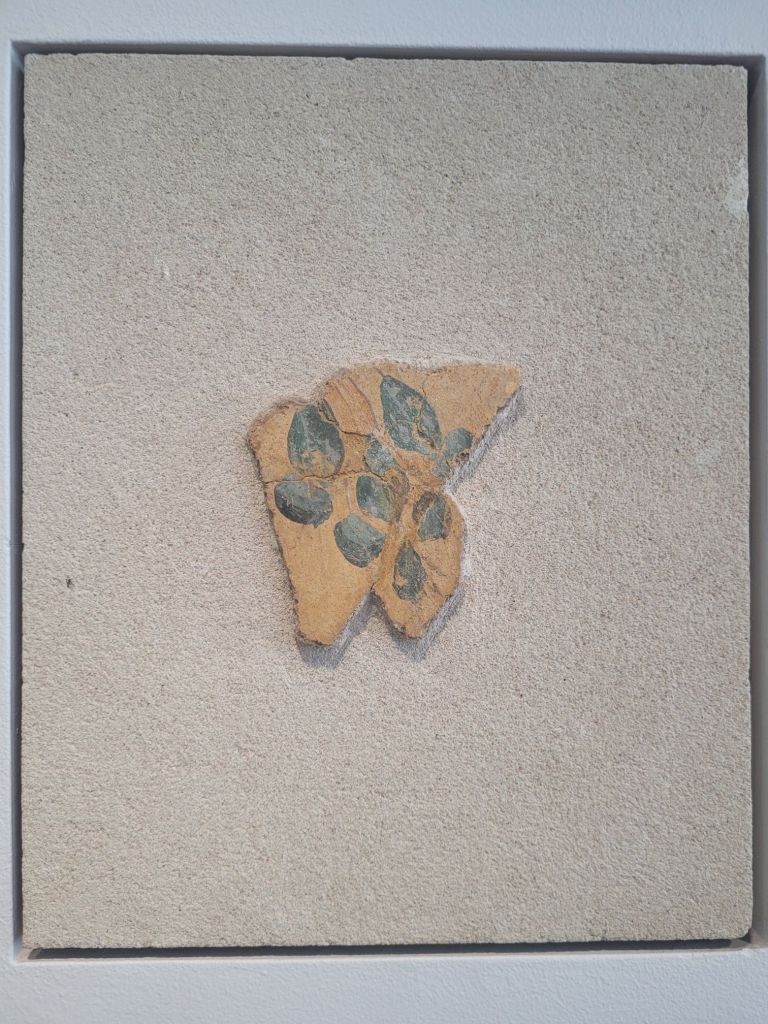

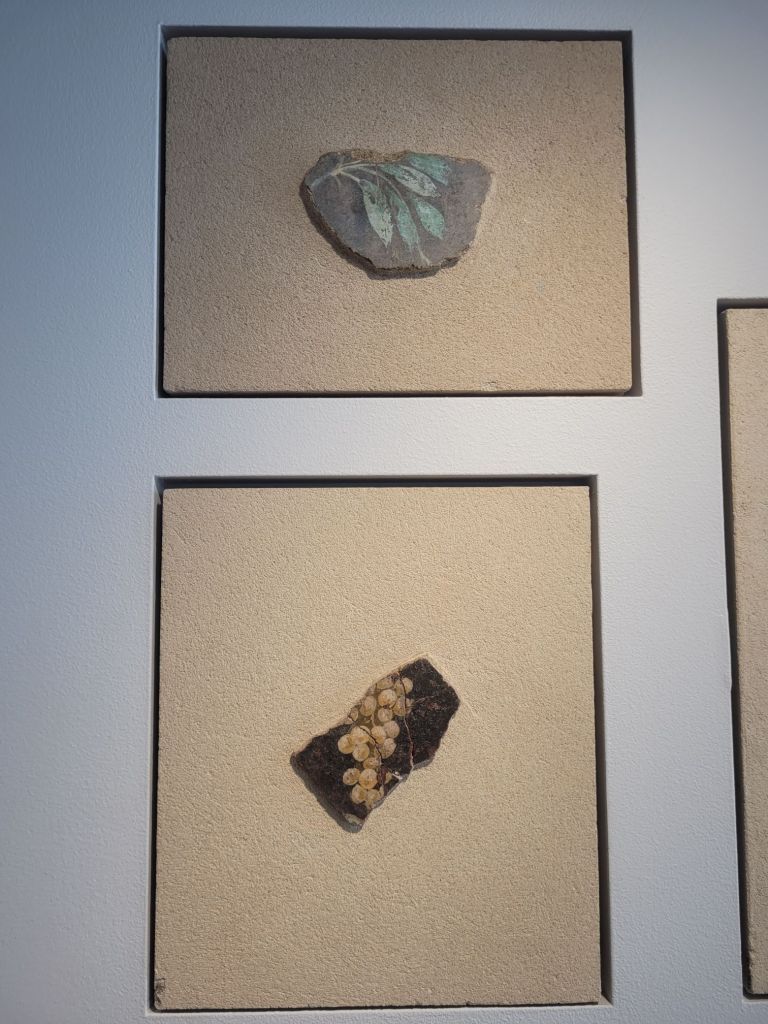

The museum is, again, built over the archological site. This isn’t as impressive as Lyon’s theatre and odeon, but it does hint at the size of the place and the collection gives a strong impression of how people lived. There is a focus on decoration such as mosaics and paintings and attempts are made to display these together – the way they would have originally been. In one display, information from Pompey has been used to reconstruct a room.

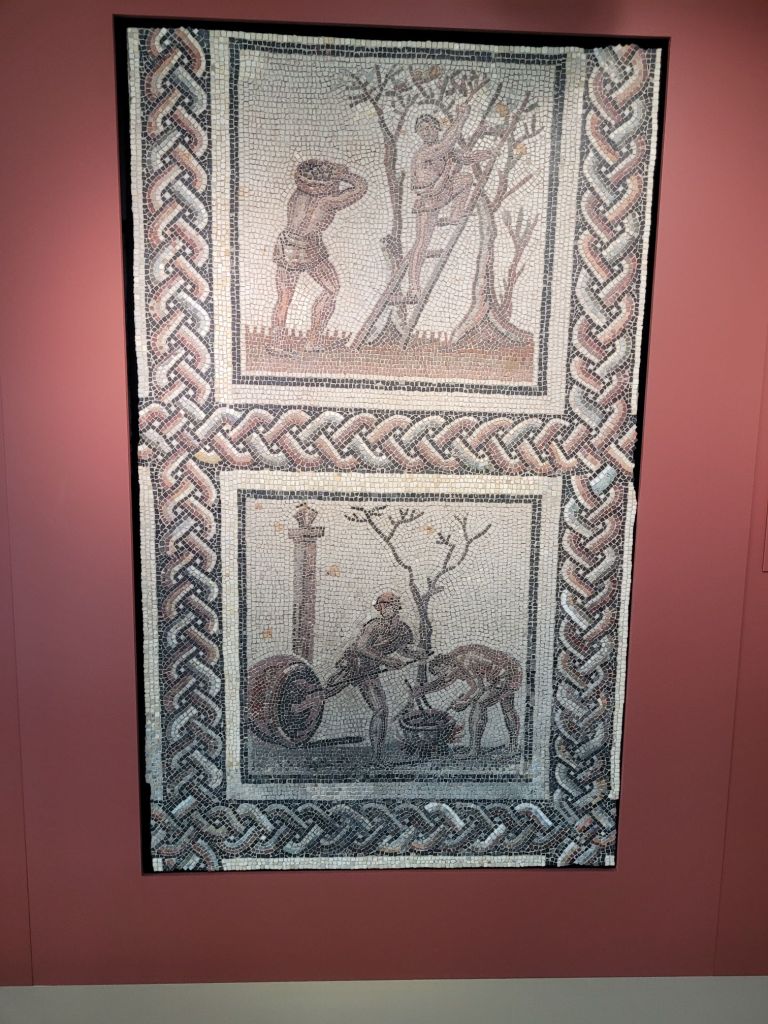

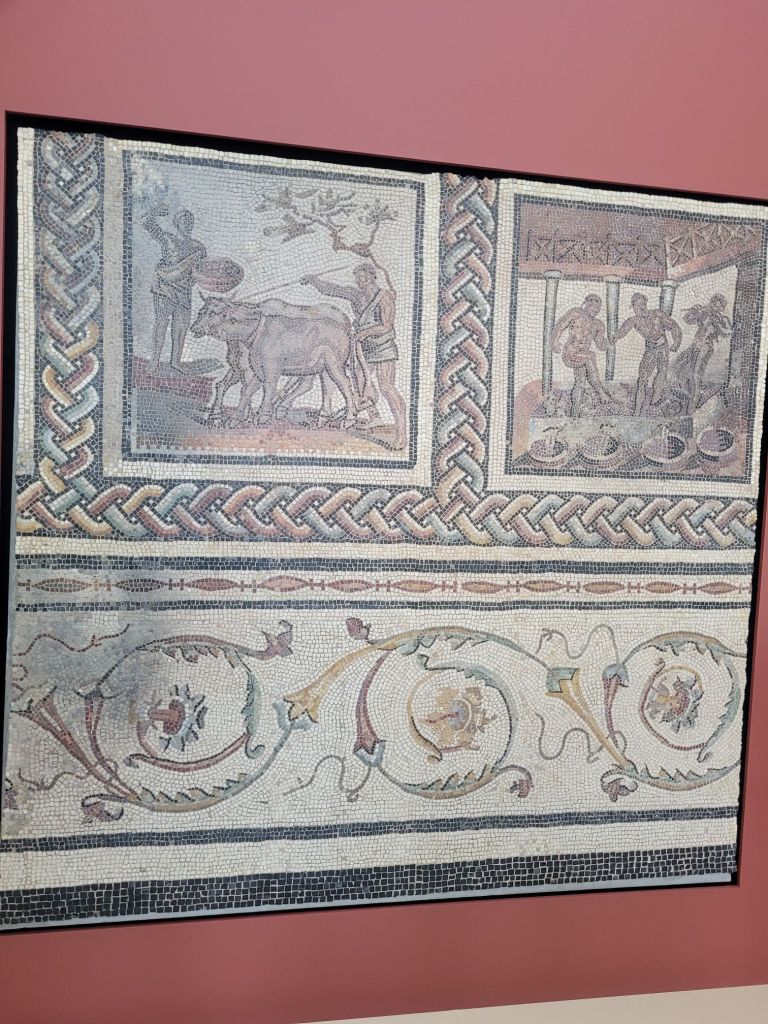

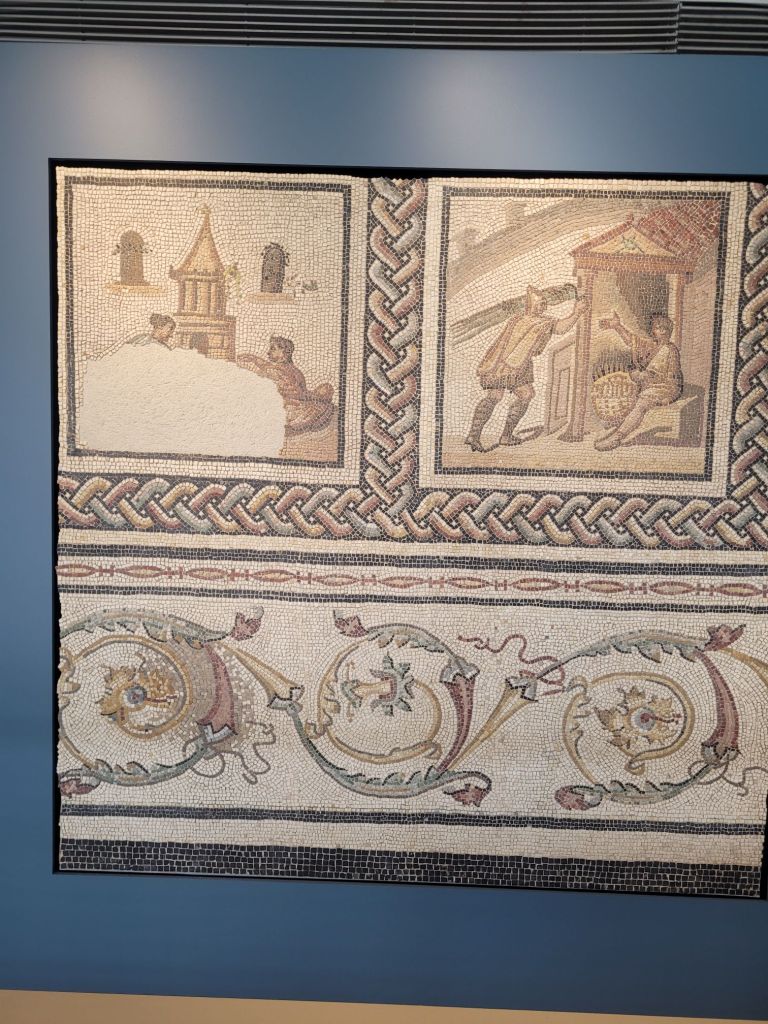

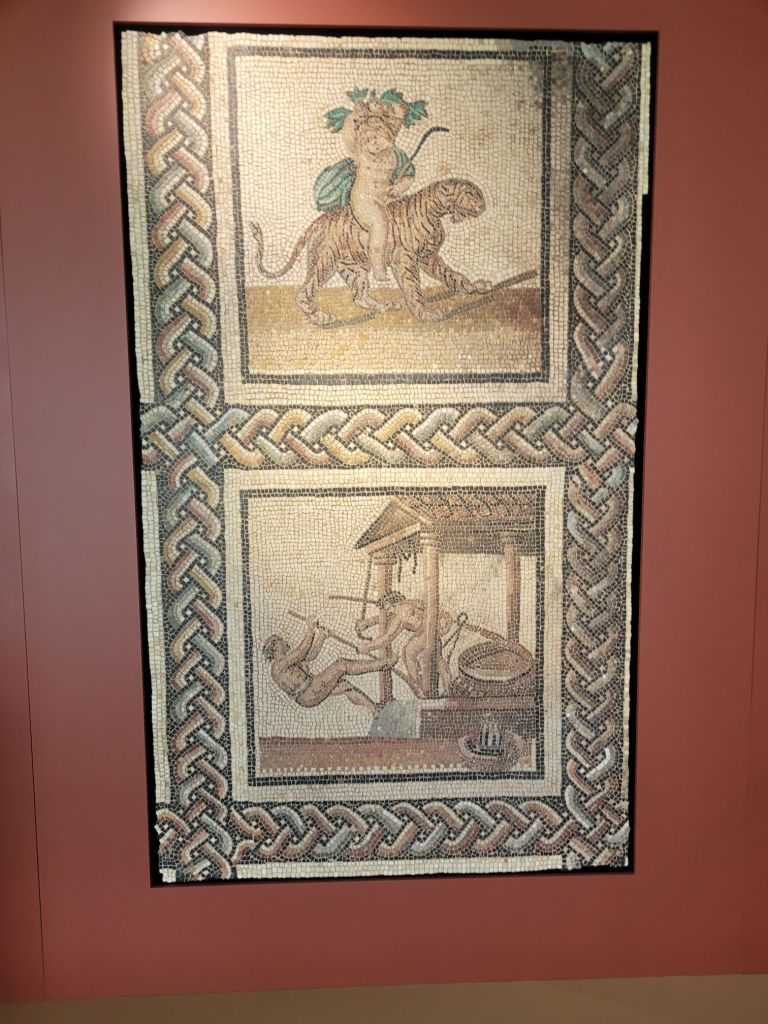

An inordinate number of mosaics were uncovered – over 250 (including the famous Four Seasons mosaic). These are varied in design and show a developing ‘local style’ unique to Vienne.

The Romans had an interest in the natural world – something I first saw in Pompey – and this museum aptly represents this in both wall paintings and mosaics. Some of the animals are breathtakingly life-like and the plants and flowers are delicate and lovely.

One of the displays features a pottery shop, destroyed by a fire, discovered with the pottery still stacked in shelves. Rather than unpack all the pottery, the shop has been reconstructed as they think it might have been. It’s very evocative of ordinary life.

Models of several houses are displayed close to the mosaic floors discovered in them (although I found it hard to connect them together at times), revealing a comfortable life for those with means.

Vienne was an important trading hub, with goods from the Mediterranean being unloaded in Arles (further downriver) and then moved upriver on river boats. Beyond the model, modern barges still transport containers up and down the Rhone.

Along the bank of the Rhone, enormous rows of warehouses collected goods for transport onwards. Models reveal the sheer size and extent of these (again, nothing was known of this until the 1960s!)

The temporary exhibit was about the Four Seasons, discovered locally and only recently returned. It’s a large mosaic depicting the changing seasons (hence the name) and the various agricultural activities associated with each season. Much of the discussion about current interpretations was in French, so tricky to follow. From what I could make out, the museum is pleased to have it back where it was discovered and important restauration and renovation work has been done which reveal much about how these mosaics were constructed.

It was interesting to compare two different museums, in such close proximity, focused on similar material. Changes in academic perceptions and how the public can be engaged by the displays are revealed by the differences in the displays, both between the museums and within the museum in Lyon: the temporary exhibit in Lyon was truly fascinating and stands in stark contrast to its other exhibits.