Over 20 million years ago, the Canaries started to emerge from the sea from East to West. (So Fuerteventura and Lanzarote as a joined mass first). All of the islands were of volcanic origin (no, still don’t know why when they aren’t on a fault line), with La Gomera emerging in the second to last phase (about 10 million years ago).

In terms of age, La Gomera could be considered one of the ‘younger’ islands, but in terms of its volcanic activity it is one of the oldest as it hasn’t erupted for two million years. But its volcanic past is in evidence in the black rocky coast and the grey/black beaches.

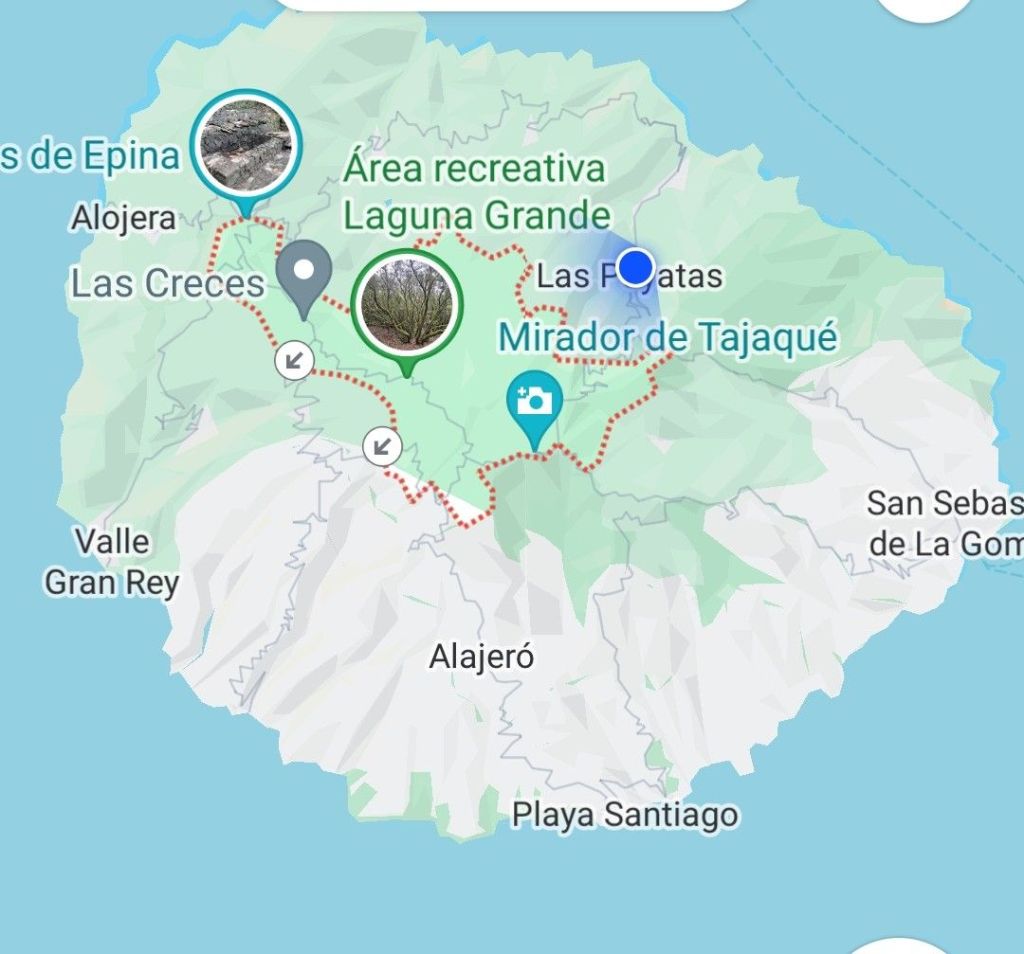

Volcanos build, the weather destroys: La Gomera has experienced two million years of erosion, which has left it with gouged ravines, sharp folds and narrow ridges. All on a steeply sloping island that tumbles into the sea. One information board called the island a ‘juicer’ when seen from above, due to how the ravines radiate out from the centre peak.

The roads are windy (both in terms of turns and twists and also the weather), the drops worryingly high and the landscape by the sea stony and brown.

However, climb far enough up and the Garajonay National Park (which covers most of the central, highest part of the island) is green, misty and damp (some would say ‘wet’). The park houses one of the last remaining Laurissilva forests (yes, like Madeira and others in the Canary archipelago), which (so I read) is actually a remnant of the Gondwanaland supercontinent.

(IE: incredibly OLD)

An aspect of La Gomera is that the top third (if not more) of the mountains are regularly shrouded in clouds.

This means that the microclimate is colder by between 6-12 centigrade from sea level, depending on the sun, and it’s very, very wet. And misty.

The forest (or is it a jungle?) walk we took was amazing.

Everything was wet and we were accompanied by the odd bird squawk and continuous dripping. Squelchy underfoot, it was rarely really muddy given how rocky it was.

But the dampness really seeped through – beading on the moss that covered the trees

dripping from the lichen hanging from the branches.

The moss was interesting as the forest seemed to start lower down, but it’s only when you got high enough that moss took over the trees as they twisted and reached for the sun.

The low lying cloud disguised how high up we were.

The island is covered in walking trails and none of them are without some ‘uppy downy’ (or a LOT of it). One trick is to get a taxi to your starting point and then walk down. This was problematic for two reasons: firstly, after the six kilometre downhill hike on La Palma, I have learned my lesson about ‘all downhill’ (it took me two days to get over the stiffness and pain) AND walking downhill in so much wet weather doesn’t fill me with joy or anticipation. So we settled for a few short circular walks linked together.

La Gomera is an odd island: some areas are barren and quite unappealing but others are quite lush. The saddest thing I saw was a ravine described by the guidebooks as ‘lush, fertile green’, but as we drove through it, it was clear that the greenness was provided by dense nopal cactus (with the odd maguey thrown in.

The island has interesting cultural history, like the whistling language that developed among the herders, and the leaping poles they used to get across gullies – both of which are being lost. It must have been an incredibly difficult place to scratch a living with such little horizontal space and given the differences in precipitation and temperature across the island. But they persevered, with a growing wine market (terracing has proved enormously useful) and a well signposted net of walking trails to appeal to walkers.

Might we return to La Gomera? The jury is out, but I doubt it.

Leave a comment