The history of the Knights Templar (or Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, to give them their full name) is entwined both with the Crusades, the many pilgrimages undertaken in the Middle Ages and (surprise) the south-west area of Extremadura (and the east of Portugal).

The Templars acted initially as a group of armed men in religious orders who grouped together to protect those going on pilgrimage to Jerusalem (and other parts of the Holy Land). They also provided a safe way to ‘move money’ across national boundaries, protection for long journeys (both by sea and land) and shock troops for the Crusades.After the Crusades, the Templars in Spain continued to protect those on pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela and they also got involved in the continuing battles against the Moors – no surprises there. Another development in Spain was that other military groups also formed, as a sort of ‘home grown’ imitation of the Templars: Santiago de Espada, Calatrava, Alcantara, Montesa … The biggest one was the Order of Santiago; this group operated in a similar area to the Templars, just slightly further to the east.

Once the Moors were dislodged, whichever Holy Order was responsible took over the settlement, building at least one large church (usually over the rubble of the mosque), a very large castle either on the Moorish fortification or on the highest point immediately next to the settlement, and developed fortifications. This pattern is repeated over and over again, either by the Templars or the Order of Santiago, throughout the area we visited.

Eventually the Templars became too powerful, too wealthy and too independent of any sort of governmental control. The secrecy of their initiation rites and vows, and a few poor decisions on the Crusade battlefields, led to the order being both disgraced and disbanded. I do wonder who got the money… As the Templars moved out of western Spain, the Order of Santiago frequently moved in, occupying the gap left behind.

The castles are vast, dominating hill-tops in the most desolate places. I have already mentioned Mertola, unusually that was a Santiago spot right from the start.

Jerez de los Caballeros followed the usual pattern of initially being Roman, then Moorish, and then Templar, only falling to the Order of Santiago after the Templars fought a bloody last stand in the Torre de Homenaje – the highest tower in the (once Moorish) castle. Those who survived the battle were punished by being beheaded, their heads thrown off the tower’s battlements. To this day the tower is known colloquially as the ‘Torre Sangriente’ the Bloody Tower.

Jerez de los Caballeros is rather unpreposessing on the outskirts (like many of these towns) but its historic center is closely focused on its historic past and work has been done to ‘tart up’ the buildings. The historical presence of both Moors and Templars is acknowledged.

The fortifications are huge and the views west are beautiful.

This was a stop-off on our way, so we didn’t spend long here. It might be worth revisiting as there are a few museums and remains, and several large churches to see.

Twenty kilometres east from Jerez de los Caballeros is another large castle on a hill: Burguillos del Cerro. We drove past it, then decided a few days later to visit: it was Monday (all museums are closed on Mondays), it was a lovely day, the castle was both free AND open…

Burguillos del Cerro was Moorish, then Templar, then belonged to the crown and was then passed to a member of the aristocracy who had land that stretched into what is now Portugal.

The town is far, far prettier than its outskirts, with lots of plaques about what belonged to who, when it was built, what it was used for… It’s also a bit of a hike to get up to the castle: the road is paved up to a point, but not drivable. After a few hairy moments navigating impossibly narrow streets that set every sensor in the car pinging, and a forced reversal uphill as a Spanish driver coming the other way refused to budge, we gave up and parked right at the bottom. And walked.

It was strenuous but lovely.

The castle itself has been abandoned for hundreds of years after being rebuilt in the 13th, 14th and 15th centuries. A bit of ‘light conservation’ has been done but certainly the safety elves have not been involved whatsoever. Visit at your peril!

The views are spectacular.

Yet another castle, spotted as we visited the little known Roman town of Regina Turdulorum, is Castillo de Reina (there is a town near Regina called Reina – I leave you to draw your own conclusions about the name similarity).

Again, initially a Roman then a Moorish fortification, this time captured by the Order of Santiago. But almost every few villages there is another castle, or ruin of a castle – it was impossible to photograph them all.

Another ‘tourist attraction’ in the area is the monastery of Tentudía, a place I was less interested in visiting. It proved both surprisingly pretty and remarkably interesting.

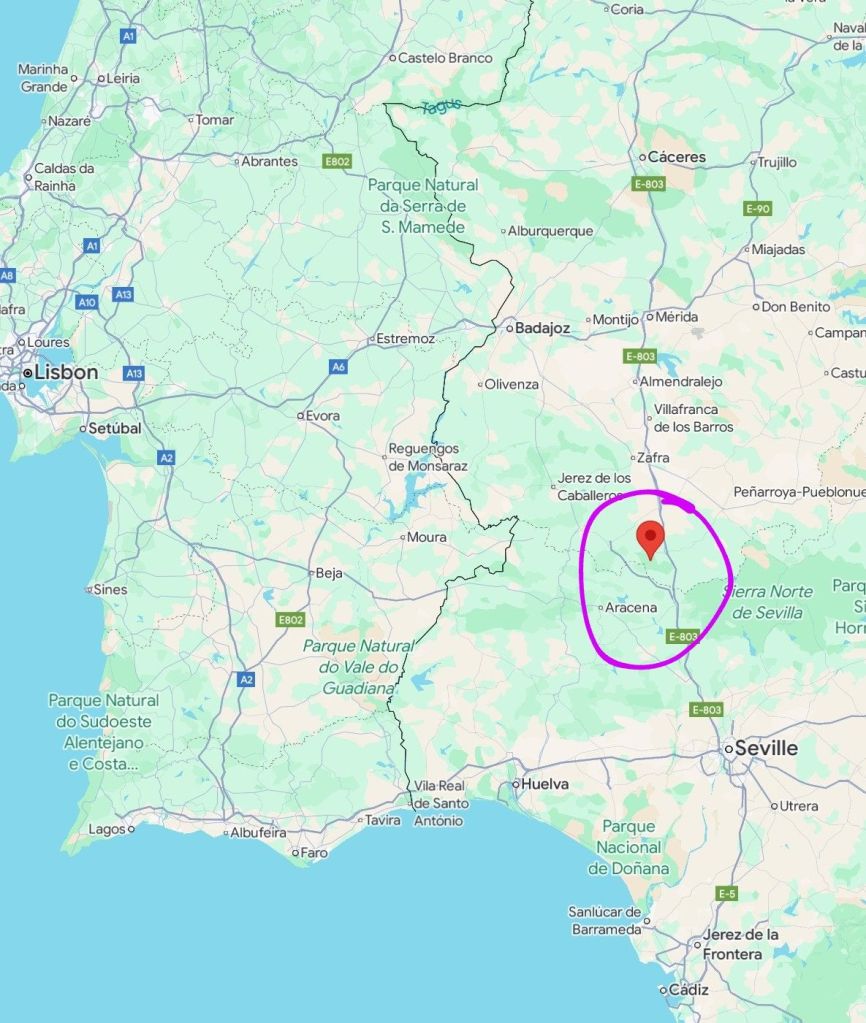

Up in the north of the Sierra Morena, the monastery is in the remote sierra Tentudía, at the highest point of the province of Badajoz – 1004 metres above sea-level. It sits on the provincial border between Huelva and Badajoz but is considered part of Badajoz.

Built in the 13th century and extended in the 16th, the monastery (which is fortified, of course) is considered a fine example of Spanish ‘mudejar’ architecture.

(Quick aside, ‘mudejar’ meaning Moorish influenced – and that’s a vast simplication.)

A hermitage was built here in response to a definitive battle between the Moors and a troop of the Order of Santiago. The battle was going in the christians’ favour, but night was falling and they needed another few hours of daylight to secure victory. Their leader fell to his knees, praying to the Virgin Mary to ‘detener tu día’ (detain your day). Daylight was prolonged, the knights were victorious, and the hermitage (and later monastery) were named ‘Tendudía’, which arises from a contraction of the prayer.

This story is represented across the area in various types of artwork. Some of it is in the museum in Seville.

Entrance is by donation and they have gone to lengths to both provide information about the Military Orders (particularly that of the Order of Santiago) but also about Medieval life (which didn’t sound particularly good for anyone, much less those on the bottom rung of society). Most of the information is in Spanish, so the signage isn’t helpful if you have no knowledge of the language.

The church is interesting for its use of tiles around the various altars and the austerity of the rest.

It’s a beautiful spot, with extensive walking, hiking, horse-riding trails, picnic spots, a children’s playground, a restaurant/cafe and well worth visiting, even if history isn’t really your bag.