And probably much of the rest of Spain too.

WARNING: this post isn’t for the squeamish, or for those who don’t appreciate seeing where their meat comes from.

Pork products – ham, chorizo, salchichon, tocino… I could go on but I’m now drooling a bit – have been associated with Spain for ever, it seems. The Romans loved pork products and embraced them but their importance lessened drastically during the Moorish period, particularly in El-Andaluz.

There is a theory that, after the Reconquista (when Isabel and Ferdinand drove out the Moors), ham – particularly the leg of ham – became an important symbol of a household’s Christianity. One popular story is that every house had to have a leg of ham hung up outside the house and it was measured regularly to confirm the residents’ religious affiliation.

This sounds apocryphal, for several reasons – flies being one of them. What about the expense? And what if the family just chopped bits off every now and then and fed it to their dog?

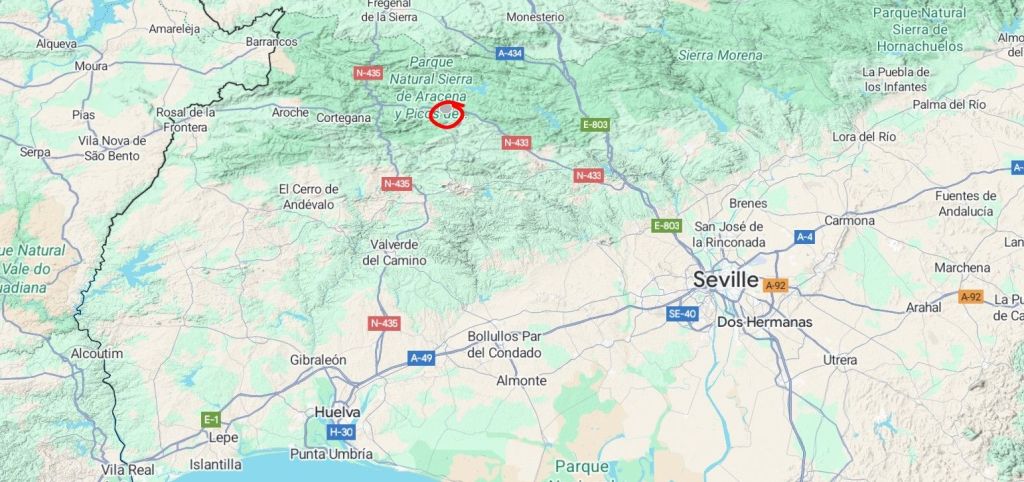

Aracena, our next stop, lies in the midst of the Jabugo area of ham production. Much of the area north of Seville is, in one way or another, linked to the rearing, raising, slaughtering, producing, cooking a wide variety of pork products. The best of them are produced from the Iberian pig – a specific breed that has developed in the Iberian peninsula (you also find them in Portugal).

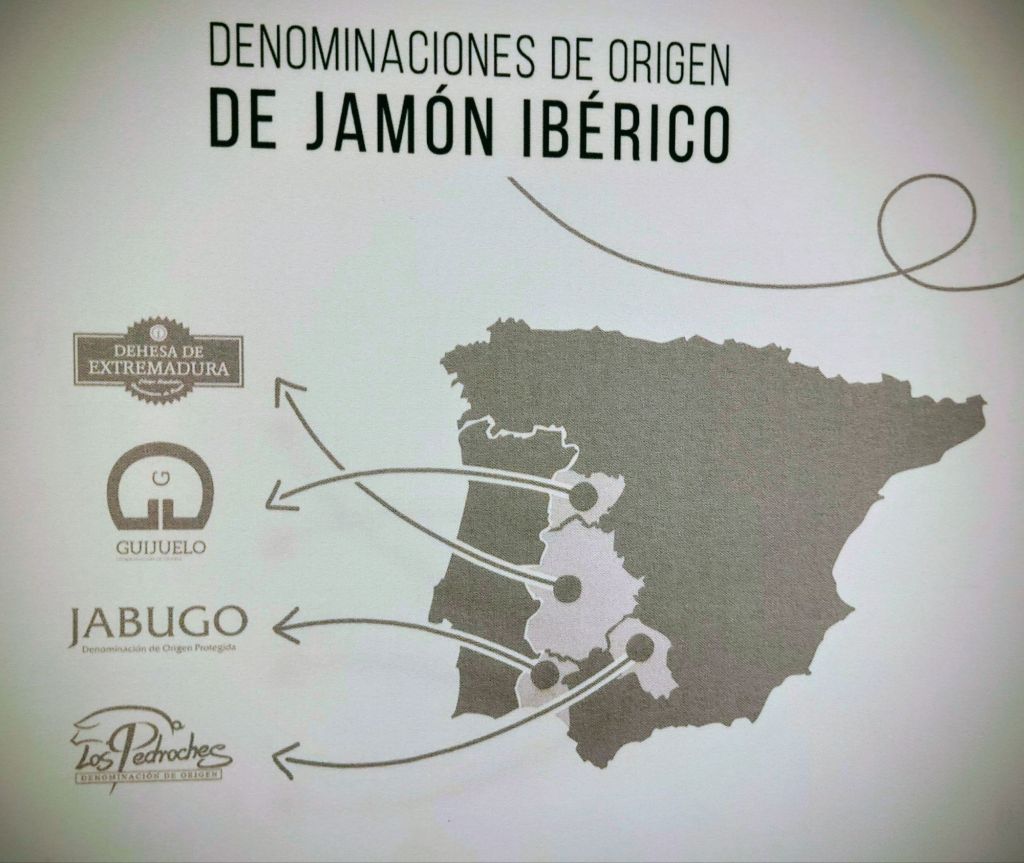

There is a whole set of rules surrounding the production and labelling of ‘real’, ‘authentic’ Iberian pigs and their products, with four areas of ‘Denominacion de Origen Protejida’ (protected designation of origin) or DOP; each area, while holding to certain minimum regulations, also adds a few of their own. All of which makes life difficult for those of us who just want to buy and eat the stuff. Like French wine, you have to know the area and the producer in order to make a good judgement about the quality. For example, the white label (the ‘lowest’ classification) is mostly grain fed, but producers in the natural park keep their pigs outside, so they do eat a mixed diet – they are probably white label because they don’t have the correct acreage for thr black label.

Aracena boasts a museum dedicated to the industry and no, it’s not at all like the ‘Museo de Jamon’ chain that just sells ham. This is a proper museum that goes through the ecosystem, the different types of Iberian pigs (there are five distinct strains), the rules (well, some of them) etc etc. It’s a bit gory in places.

There are also producers who offer ‘ham tours’, with a tour of the ‘dehesa’, the factory and a tasting session. And every producer ‘bends’ some of the rules in subtle ways designed to confuse. And some of the rules are just plain dumb (more of this later).

The Jabugo denomination has the strictest rules.

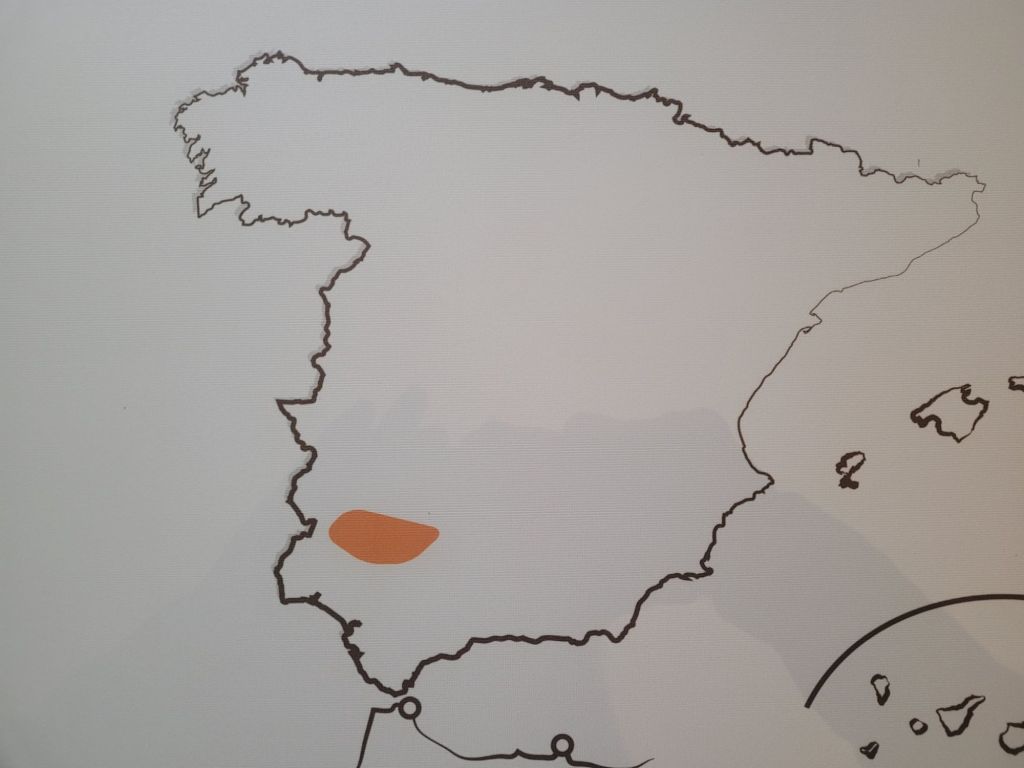

The Iberian pig itself is a good starting point for this topic. The five strains are all perfectly adapted to living in the semi-wild dehesa, eating acorns and fending for themselves. Backing up a bit, the dehesa is an actively managed wild environment with a mixture of trees and grassland and used for grazing animals. In the Natural park, nothing can be done to the dehesa without prior permission: pruning, removing dead wood, mushroom picking – anything – even on privately owned land.

Of the five Iberian strains, four have the distinctive ‘pata negra’ or black foot – their hooves are black. The fifth strain, the Manchado de Jabugo, is now considered a rare breed: it’s a red-haired pig, with blotches, and a lighter hoof. Because of the distinction conferred by the ‘pata negra’, hams from these pigs tend to be overlooked.

The ham tour we took with Eiriz started off in the dehesa, with a few cute pigs trotting around.

They were fairly tame, very muddy and overly keen to rub against everyone’s legs and explore their shoes, thus transferring a portion of mud from them to us. They were also extremely chatty, grunting away as they trotted over to say hello. At one point, one flopped down in front of the guide and waiting for a belly rub.

Now, rules.

The rules cover: the purity of the strain of pig; how long they have spent outside fending for themselves with no extra feeding; how much land they have to roam on; how much each ham weighs at the start of the drying process and what percentage of loss occurs during the drying process; the production process itself, for example, how long the hams spend in salt, the temperature at which they are aged, no artificial control of humidity or temperature… The list is fairly extensive and at any point, the pig or its products can be considered ‘outside the norms’ and declassified. Declassified products are labelled with blue labels, and can sometimes be purchased from a producer depending on the time of year. Because the blue label doesn’t carry the premium label, it loses the premium prices.

The very, very best quality hams are ‘double black label’: 100% Iberian pigs, having spent two seasons out in the open eating acorns and whatever else they can find and fulfilling all the weights and measures laid down by the DOP. The Jabugo DOP is the only one that awards a double black label. The sweet pigs running around behind the Eiriz factory were declassified, as they didn’t have the minimum required acreage.

The ‘montañera’ is the season the pigs spend outside, starting from October, when the oak trees start to drop their acorns. The pig’s favourite acorn is the Holm oak, it’s sweeter; eating nine and a half kilos of these acorns results in a gain of one kilogram of body weight. They also eat chestnuts (and there are lots of chestnut trees in the Jabugo DOP), olives, and anything else available. Cork oaks ripen latest, they are also more bitter, so the pigs only eat these when there isn’t anything else; it takes 14 kilos of cork oak acorns to add one kilo of body weight. The body weight issue is vital, as the pigs can’t go to slaughter until they reach a certain weight – and clearly there’s the whole issue of how much each ham weighs. During the montañera, the pigs can gain up to two kilos a day – which is incredible when you think they are also covering at least five kilometers a day grubbing for food.

The dehesa has a mixture of trees and even though the pigs aren’t keen on them, cork oaks feature heavily. This is partly because they provide a second income stream, but also because they are fire resistant, so useful to have during dry seasons.

All the pigs destined for pork production are sterilized, both male and female. The males because testoterone affects the flavour of the meat, and the females because they don’t want them impregnated by the wild boar that roam the area. I won’t go into detail, but the description of the sterilization process was off-putting in the extreme. But once this is over, and all the various tags are attached, the pigs are left very much to their own devies, with minimal intervention.

The Eiriz firm has been producing hams and other related products for a long time. The room where the meat was processed has been left with a display of implements, and a large reproduction of an old photograph of the butchery process hangs above the original location. Yes, it’s a trifle gory, but if you can’t face what happens to the animal and it’s body during processing, then you have no right to eat the results.

(In my humble opinion.)

The tour of the factory was, thankfully, on the tame side as they weren’t doing much of anything other than drying and cleaning. Maybe they were resting up before the slaughter season, which starts January and February.

Once the hams, shoulders, loins and other select bits have been removed from the carcass, they are salted. It’s a physical process that involves a huge amount of salt – from the salt pans in Sanlucar, funnily enough – a whole room built up of salt and cuts of meat which are restacked and turned half way through the two week process. The salting room was being readied for the next batch – when in use, it’s filled to the top of the red section.

The image on the right is of a picture they have hung in the room to show the process – you can just about make out the salt heap with hams stuck in it.

Once out of the salt, they are washed and dried (the only poit in the process where there can be artificial temperature management) and then they are prepared for the longer, slower drying process. Throughout the drying process (remember, no artificial controls on humidity or temperature), the meats are monitored carefully.

Over a period of time a bacterial bloom grows on them and each product is regularly painted with sunflower oil to control the bloom, which can be clearly seen in the images below. This is done by hand, with a paintbrush.

Every pig has an ear tag with a unique number. Every ham and ‘paleta’ is tagged to the same number – the hams are the back legs, the paletas are the front legs. The numbers are all tracked. For a ham or paleta to be considered a double black label, all the criteria need to be fulfilled. The producer notifies the authorities about the number of products they think will become double blacks, along with the serial number of the pig they came from. They then receive the exact number of labels, with a matching serial number, so that there is full traceability and accountability. One quirk of the system is that a whole paleta or ham can be a double black label. Ready sliced ham, sold in vacuum packs, can also be double black label but ready sliced paleta cannot carry the double black label. Makes enormous sense…

One ham takes four years to produce – two years of montanera and two years of curing – and a lot of manual labour. Each ham costs about 400 euros to produce. Last year the factory was broken into and 200,000 euros worth of products were handed out through a broken window, destined to be separated from their identifiers and sold on the black market. It’s definitely a premium product.

Ham (be it lomo, paleta or jamon) is worth eating for more than just its fabulous taste. After a rather brutal start, the pigs spend most of their lives roaming free, with no vaccinations, no extra treatments, no additives in their feed and minimal human interaction. They roam naturally, and the exercise ensures that they don’t build up excess fat: what fat they do put on is distributed through the meat (thus the rules about acreage). The pigs can be grain fed through the summer if the weather has affected their food supply; when they do feed them grain, the quantity is carefully controlled so that they don’t gain any weight. Once they enter the montañera, no extra food can be given. The pigs are unique in the amount of monosaturated fat and oleic acid their meat contains. In the very best products, the oleic acid crystallizes out as small white specks on the surface of the meat.

As with everything, you get what you pay for but you also have be armed with a bit of knowledge in order to correctly interpret the labels. I have been to the ham museum twice, did the tour, made careful mental notes and asked questions. I know that black is the best, then red (75% Iberian), green and white are partially grain fed… I know stuff.

But I still became completely unglued in the ham aisle!